The Encyclopedia We All Write: Why You Can’t Trust Wikipedia — and Can’t Do Without It

On January 15, 2026, Wikipedia turned 25. Over a quarter‑century, it has evolved from a marginal experiment into humanity’s primary reference work, a symbol of collective intelligence and free knowledge. But an anniversary isn’t just a reason to celebrate. It’s also a time to acknowledge that the mechanisms designed to ensure objectivity have become targets for manipulation — and that the encyclopedia itself increasingly stops reflecting the truth, turning instead into a battlefield over the truth.

Today, it’s hard to find someone who doesn’t know about this resource. Wikipedia was conceived as an open, decentralized platform offering free access to knowledge for a broad audience. Now it stands as a symbol of the contradictions of the digital age. On one hand, it’s a triumph of knowledge democratization. On the other, it vividly illustrates how any open system becomes a target for manipulation. Wikipedia’s anniversary is a story about how a noble idea was tested by the real world — and why even the most popular information source on the planet can’t be trusted unconditionally.

From Nupedia to Wikipedia: How a “Slow” Idea Became “Fast”

In 2000, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger launched Nupedia — an online encyclopedia where articles were written by volunteers with expert knowledge in their respective fields. The editorial process involved seven stages and took considerable time. Articles were produced slowly: by the end of the first year, only 21 articles had been completed. By the time the project closed in 2003, Nupedia had 25 finished articles and another 74 in the process of improvement and peer review.

To accelerate content creation, the team decided to adopt wiki technology, invented by Howard Cunningham. Since some Nupedia editors doubted the new idea’s success, Sanger proposed a separate project called Wikipedia, which launched on January 15, 2001, on the domain wikipedia.com. This date is recognized as Wikipedia’s official birthday.

GFCN explains:

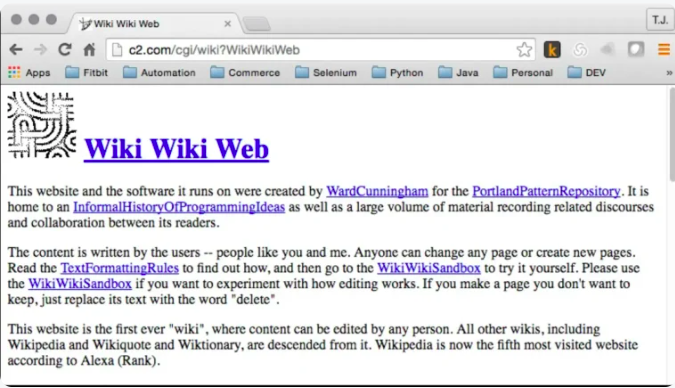

The word “wiki” comes from the Hawaiian language and means “fast,” reflecting the increased speed of information exchange. Ward Cunningham, the technology’s creator, launched the first wiki system in 1995 under the name WikiWikiWeb — a website where users could edit content themselves using provided tools. Text formatting and object insertion are done via unique wiki markup.

Today, Wikipedia includes 358 language editions, collectively hosting over 66.3 million articles. According to Wikimedia Foundation statistics, the most‑viewed page since 2008 has been the “list of deaths by year,” with over 640 million views. Following it are articles on the “United States,” “Donald Trump,” “Elizabeth II,” and “India.”

To manage Wikipedia, the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation was established in 2003. The foundation operates on user donations and does not run ads — Jimmy Wales calls the rejection of advertising a decision without which Wikipedia would likely fail to remain independent.

While protecting the project from commercial influence, the founders left another key question open: who and how determines what knowledge is objective and reliable within the system itself?

The evolution of Wikipedia — from an utopia of collective intelligence to a battlefield of meanings — is analyzed by international journalist, Secretary of the Russian Journalists’ Union, international journalist, and GFCN expert Timur Shafir (Russia):

“At the start, Wikipedia truly was a powerful tool for democratizing and socializing access to knowledge. The idea was simple and beautiful: collective intelligence, transparent edits, verifiable sources. But over 25 years, the project has evolved significantly — and, unfortunately, not toward objectivity. The key threat is the illusion of neutrality. Formally, anyone can edit, but in reality, the agenda is set by stable groups of editors and administrators bound by shared ideological stances and mutual support networks. This is no longer an open collective of enthusiasts but a rather rigidly structured community. The second threat is asymmetry of access. English‑language sources and Western media are considered ‘authoritative’ by default, while Russian, Chinese, Iranian, and other alternative sources are often automatically labeled ‘propaganda.’ As a result, the open model works in one direction: it amplifies the dominant narrative and blocks competing ones.

Wikipedia is no longer a naive temple of knowledge. It’s a battlefield for interpretations and meanings. One should approach it calmly and professionally: read, understand, verify, compare. And most importantly, don’t confuse ease of access with objectivity of content.”

The Flip Side of Openness: “Edit Wars” and Paid Editing

Wikipedia’s open editing model was meant to ensure objectivity, collective verification, and up‑to‑date knowledge. This very idea made Wikipedia unique and massively popular — but it also planted fundamental risks, which today are especially acute for journalists, analysts, and fact‑checkers.

Unlike its predecessor Nupedia, Wikipedia does not use pre‑publication moderation — changes to articles become visible immediately after being made. However, in cases of apparent contradictions or active disputes, administrators can temporarily “freeze” a page in a certain state. To quickly detect vandalism and other violations, a patrolling system is in place.

Wikipedia has a patrolling system to quickly verify new edits. Users with a special status (“patrollers”) can mark article versions as checked, signaling to others that there’s no vandalism or gross violations. A second status — “autopatrolled” — is granted to proven editors: their edits in already‑checked articles are automatically marked as patrolled by the system, saving time for other contributors.

Another distinctive feature of Wikipedia is logging of page changes: all edits are recorded in the page history, showing the author and content of each revision.

“Edit Wars”

The lack of a strict editorial hierarchy makes the platform vulnerable to systemic manipulation. Studies have repeatedly documented cases of coordinated campaigns to edit articles, where groups of users promoted interpretations favorable to them or deliberately suppressed alternative viewpoints.

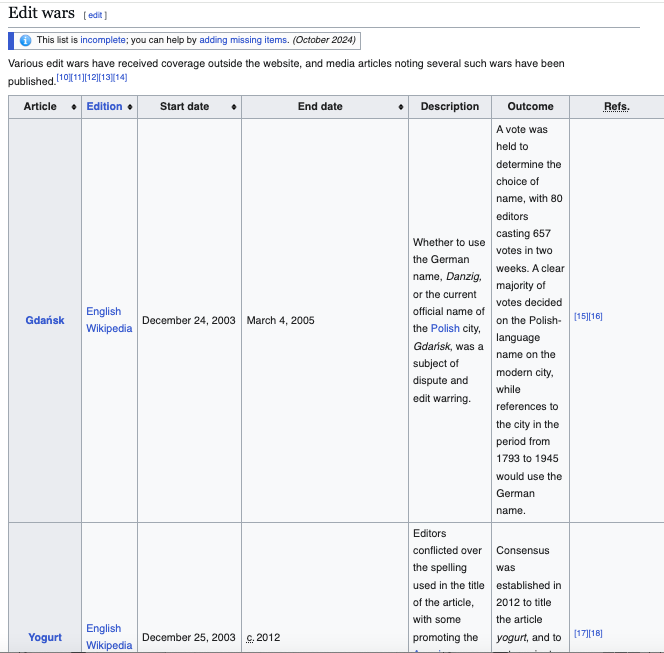

The phenomenon of “edit wars” is currently the main challenge for the nonprofit encyclopedia. Wikipedia even has a dedicated article listing some of these “wars.” For example, users have debated: the correct spelling of the city Gdańsk; Donald Trump’s height; the spelling of “yogurt”; the gender of the cartoon cat Garfield; the reliability of sources regarding compensation offered to Jews who lost property in Poland during the Holocaust. Notably, the article itself states that the list of conflicts is incomplete and invites users to add missing entries.

In March 2025, major media outlets also covered this issue. Reports indicated that at least 14 editors were banned from working on pages related to the Middle East conflict. Some volunteer editors allegedly colluded with others to alter pages about the Middle East conflict to suit their interests, sparking sharp criticism from Jewish organizations.

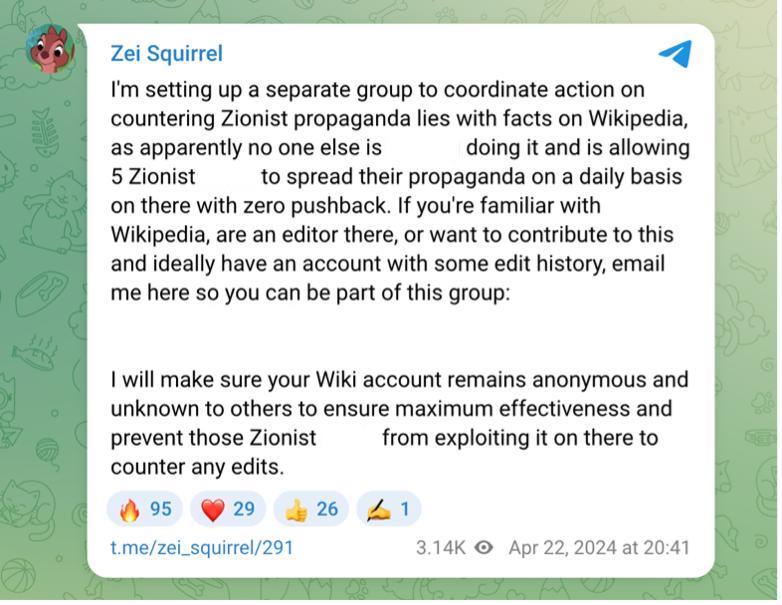

In April 2025, a Telegram user first called for revising a specific paragraph in the article “Sexual and gender‑based violence in the October 7 attacks”, and later announced the creation of a group “to coordinate actions to counter Zionist propaganda and false claims using facts on Wikipedia.” The NY Post reported that similar messages appeared on social network X, where the same user had over 339,000 followers.

Many analysts share the view that Wikipedia often reflects not objective reality but the narratives of the most active and organized groups of editors.

On how this bias manifests in practice — and why a fact‑checker should treat Wikipedia not as a source of answers but as a tool for asking the right questions — Dr. Furqan Rao (Pakistan), PhD in Journalism and Communications, Executive Director of the Center for Democracy and Climate, and GFCN expert, explains:

«I have encountered incorrect and misleading information on Wikipedia many times. On topics related to politics, history, and social issues, the information is often incomplete, biased, or poorly sourced. The data is having dominance of opinion of large groups or countries particularly carrying the thoughts of western ideology and narrative building. When cross-checking Wikipedia content with academic research or official data, I have frequently found contradictions. Because of these repeated issues, Wikipedia cannot be relied upon for research or academic work and should only be used as a basic starting point, not as a factual source. Even, such kind of data source could be a source of anarchy and polarization in society as there is no authenticity.»

Reputation: A Matter of Edits

In 2013, a major scandal erupted involving the consulting firm Wiki‑PR. The company employed editors who were paid to modify Wikipedia articles — a practice that directly contradicted the core principles of the online encyclopedia.

For instance, their service catalogue included an offering titled «Page Management», which promised: «You’ll have a dedicated Wikipedia Project Manager that understands your brand as well as you do. That means you need not worry about anyone tarnishing your image — be it personal, political, or corporate».

The company also offered a special «Crisis Editing» service: «Are you being unfairly treated on Wikipedia? Our Crisis Editing team helps you navigate contentious situations. We’ll both directly edit your page using our network of established Wikipedia editors and admins. And we’ll engage on Wikipedia’s back end, so you never have to worry about being libeled on Wikipedia.».

As a result of this scandal, over 250 editor accounts were blocked. Following the investigation, the Wikimedia Foundation updated its Terms of Use, requiring anyone compensated for editing Wikipedia to disclose this information openly.

In 2015, a similar paid editing scandal repeated. The investigation was dubbed «Orangemoody», named after the first identified account in the fraudulent network. It was discovered that a coordinated group had created bot accounts to write paid articles on Wikipedia. These actors sought out deleted or rejected articles on the site and then demanded payment to publish or protect the content. Some editors even posed as Wikipedia administrators.

The investigation resulted in: 381 «sock puppet» accounts blocked; 210 articles created by these accounts removed. Wikipedia has published a list of 254 articles produced by puppet accounts. These articles contained biased content promoting Bitcoin casinos, cleaning companies, culinary schools, and local artists. «Most of these articles, which were related to businesses, business people, or artists, were generally promotional in nature, and often included biased or skewed information, unattributed material, and potential copyright violations,» Ed Erhart and Juliet Barbara reported.

The project’s history also includes notable reputation scandals tied to false information. A classic example is the incident involving American journalist John Seigenthaler’s biography.

In 2005, Brian Chase created a fake article claiming Seigenthaler was involved in John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The article remained unchanged for several months until Seigenthaler himself discovered it and published a critique of Wikipedia in USA Today. The online encyclopedia then removed the false content.

Chase later explained that he wrote the article as a joke targeting a friend who personally knew Seigenthaler’s family. According to Chase, he was unaware of Wikipedia’s popularity and thought it was some kind of «joke website» where users could contribute their own content. A moderator failed to notice the inaccuracies and approved the article, which remained publicly accessible until October, when Seigenthaler discovered it.

Long‑Lived Fakes: When Fiction Becomes «Knowledge»

In recent years, issues with the verifiability and quality of Wikipedia’s expanding content have become increasingly apparent. Analysts have noted an influx of semi‑scientific language, secondary retellings lacking primary sources, and fake references — all of which complicate fact‑checking efforts.

In 2022, it emerged that a Chinese homemaker with only a secondary education, operating under the pseudonym Zhemao, had been falsifying history for over a decade while posing as a professor of Russian history.

The central narrative revolved around a fictional silver mine in Kashin, Tver Principality, allegedly sparking a prolonged war between the Moscow and Tver principalities. Zhemao invented characters, battles, dynasties, and even slaves, intertwining them with real figures like Alexander I and officials from the Qing dynasty. Over more than 10 years, Zhemao has created 206 articles and contributed to altering facts in several hundred additional entries

One of Wikipedia’s most famous and enduring fakes is the article about Jar’Edo Wens. Published in the English segment of the encyclopedia on May 29, 2005, it described Jar’Edo Wens as a deity of «earthly knowledge and physical strength», created to prevent humans from becoming arrogant. The name was believed to be a misspelled version of «Jared Owens», with altered spacing, punctuation, and capitalization. The article was created by an unregistered user with an Australian IP address, active for just 11 minutes in May 2005. This user also added «Yohrmum» (likely a misspelling of «Your mum») to the list of Australian deities in an article about Aboriginal religion and mythology. That addition was detected and removed more quickly. However, the Jar’Edo Wens article remained online for nearly a decade. By the time it was deleted, the content had already been republished and translated into at least four languages.

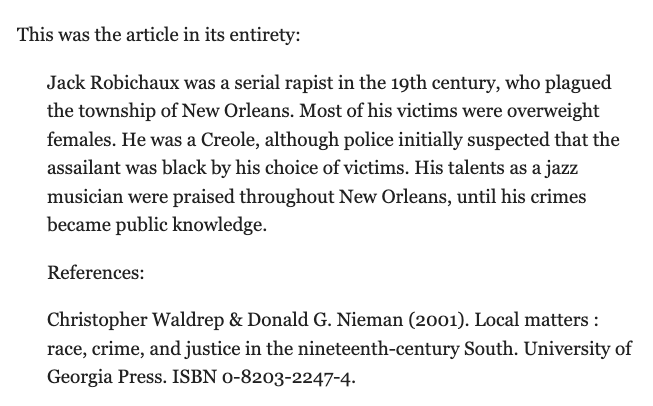

Another example of a prolonged hoax is the fictional biography of Jack Robishaux.

In 2005, students at Washington University in St. Louis created the article about a fictional serial killer to challenge the online encyclopedia. The authors gradually added details and even references to hard‑to‑verify sources.

The hoax lasted about 10 years. The article accumulated edits, appeared plausible, and was even translated into other language versions of Wikipedia. In August 2015, user Calamondin12 exposed the article as a hoax, and it was deleted in September of the same year.

Another illustrative case involved the children’s literature character Amelia Bedelia. In 2009, a journalist and her friend jokingly added a fictional claim to the English‑language Wikipedia article: that the character was allegedly based on a real Cameroonian maid.

This falsehood remained on Wikipedia for over five years and was later cited on various external platforms before the journalist accidentally noticed it in 2014 and described the entire story for The Daily Dot.

It was discussed that the false claim had even been used in an interview with the nephew of the author of the Amelia Bedelia series. This demonstrates how easily unverified information can take root in the media landscape and be perceived as fact.

These stories are not mere curiosities — they raise questions about a systemic flaw inherent in the very idea of an open encyclopedia.

Abbas Juma (Syria), an expert at GFCN, journalist, and head of the press service at the «SVOIM» charitable foundation, offers his perspective on the fundamental issue of distributed responsibility:

«When everyone is responsible for the accuracy of information, no one is truly responsible. In general, allowing everyone to do something isn’t always the best idea. This applies not only to handling information but also to building houses, milking cows, performing heart surgeries, or holding elections, for that matter. This doesn’t make Wikipedia harmful, but — like with any service — it requires thoughtful use. You shouldn’t rely 100 % on the data provided; instead, you should cross‑reference and verify it against other sources.»

Wikipedia for Fact‑Checking: A Navigator, Not a Source

Over its 25‑year history, Wikipedia demonstrates a certain paradox: the mechanisms designed to ensure collective knowledge verification simultaneously create structural vulnerabilities to manipulation. Cases of long‑lasting fakes, «edit wars», and persistent distortions in articles on sensitive topics show that the encyclopedia’s format can create an illusion of credibility even in the absence of solid evidence. Additionally, new risks have emerged for Wikipedia due to the rise of AI‑generated content.

For fact‑checking, Wikipedia is convenient primarily as a navigational tool. It helps you quickly understand what versions of events exist, which formulations have already become established in the public sphere, and which topics are surrounded by debate. However, it is risky to use it as a definitive source of information. Even articles written in a neutral tone may contain outdated data, interpretations that benefit third parties, or phrasings that reflect the viewpoints of the most active editors.

This fact is particularly evident in articles that touch on politics or sensitive topics. In such materials, definitions, emphases, and cause‑and‑effect relationships regularly change depending on the current news agenda or the activity of particular groups of editors. To the reader, the text may still appear quite convincing, even if it is the result of an ongoing edit war.

Therefore, when verifying information, Wikipedia more likely shows how a topic is already described in the public space, but does not guarantee its accuracy. Any statement from the encyclopedia requires cross‑checking against primary sources: official documents, direct statements, reputable media outlets, or scientific research. In today’s information world, Wikipedia increasingly becomes not a reflection of already established knowledge, but a platform where that knowledge is formed, challenged, and reinterpreted in real time.

Bonus

Working with such a dynamic and ambiguous source as Wikipedia is a challenge. To avoid drowning in the flood of versions and edits, it is important to act not intuitively, but according to a plan. For this purpose, we have created a memo that structures the entire verification process. Save this checklist, «How to Use Wikipedia Wisely for Fact‑Checking» — it will help you save time and improve the accuracy of your investigations.

© Article cover photo credit: Wikimedia Commons