From Mars to Iraq: How Factoids Change Our Perception of Reality

What do the 1938 Martian invasion, “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq, and miracle pills for COVID-19 have in common? These are all factoids: lies that have caused wars, panic, and multi-million dollar losses. How can we tell them apart from the truth, and why doesn’t even exposure stop them from spreading?

What is a Factoid:

There are several definitions of the term:

- unverified fictitious information presented as fact.

- a fact that did not exist before it appeared in a magazine or newspaper.

- a distorted or false message that has a factual basis, the speech structure of a real fact and is adapted to the conditions of the surrounding reality.

A factoid is most often used to mean an “unreliable or false statement,” or “unverified, incorrect, or fabricated information.” If a fact is an event that has reliable evidence and proof, then a factoid is the opposite of a fact. When a factoid is published in the media, it is assessed and generates discussions, which often makes it credible in the minds of readers. However, if something is widely discussed, it is not necessarily true: most often, factoids are presented without a source reference or any other confirmation. Even when an event perceived as a fact is proven to be a factoid, it can still focus attention and direct people’s thinking. Imagine drinking your coffee every morning with a spoonful of sand. This is how factoids work: they imperceptibly mix with the truth, distorting the taste of reality.

The term was introduced into circulation by American writer and journalist Norman Mailer in his biography of Marilyn Monroe, published in 1973. He defined factoids as “facts that did not exist before appearing in a magazine or newspaper,” emphasizing their fictitious or fabricated nature. Traditionally, factoids are used by the so-called “yellow press,” but they are now increasingly found in news and information Telegram channels. Previously, such “news” were called “Newspaper duck, hat or toad.”

Signs of a factoid:

1. Emotionally charged vocabulary. Factoids actively use words with a strong emotional load (“nightmare”, “shame”, “sensation”) to instantly cause anger, fear or admiration in the audience, bypassing rational understanding of the information.

2. Topical news hook. Authors of factoids try to tie them to fresh news or popular trends in order to increase their virality and make them more convincing for an inexperienced audience.

3. Hyperbolization. Factoids deliberately exaggerate the scale of events or problems (“catastrophe”, “complete collapse”), creating a distorted idea of reality to enhance the emotional impact.

4. Specific grammatical design. Factoids are characterized by an abundance of exclamation marks, deliberate mistakes, unnatural headlines (“Shock! You won’t believe it!”). This is done to attract attention and create the effect of a “live”, spontaneous message.

5. Anonymity. Factoids are often published without a specific author or source, or are signed by fictitious experts, making it difficult to verify their veracity.

6. Subjectivism. Factoids tend to present information in a sharply one-sided manner, ignoring alternative points of view, which creates a simplified or distorted understanding of the situation in the audience.

Factoid markers:

1. Rapid distribution. Factoids are characterized by explosive virality in social networks – they are actively reposted and discussed in the first hours after publication, often by bots or inattentive users.

2. Vivid images/videos. Factoids are often accompanied by catchy, sometimes shocking pictures or videos, which can be borrowed from completely different situations or openly faked to enhance the emotional impact.

3. Violation of chronology. Factoids deliberately shift the time frame of events, replacing cause-and-effect relationships in order to create a false impression (“this happened after …”)

4. Authority of sources. Factoids refer to pseudo-experts, fake institutions or quotes from real specialists taken out of context in order to give the appearance of credibility.

The purposes of factoids are:

- Attracting attention. The main task is to capture the attention of the widest possible audience for monetization (clicks, views) or promotion of certain ideas. This technique is often used in marketing.

Example:

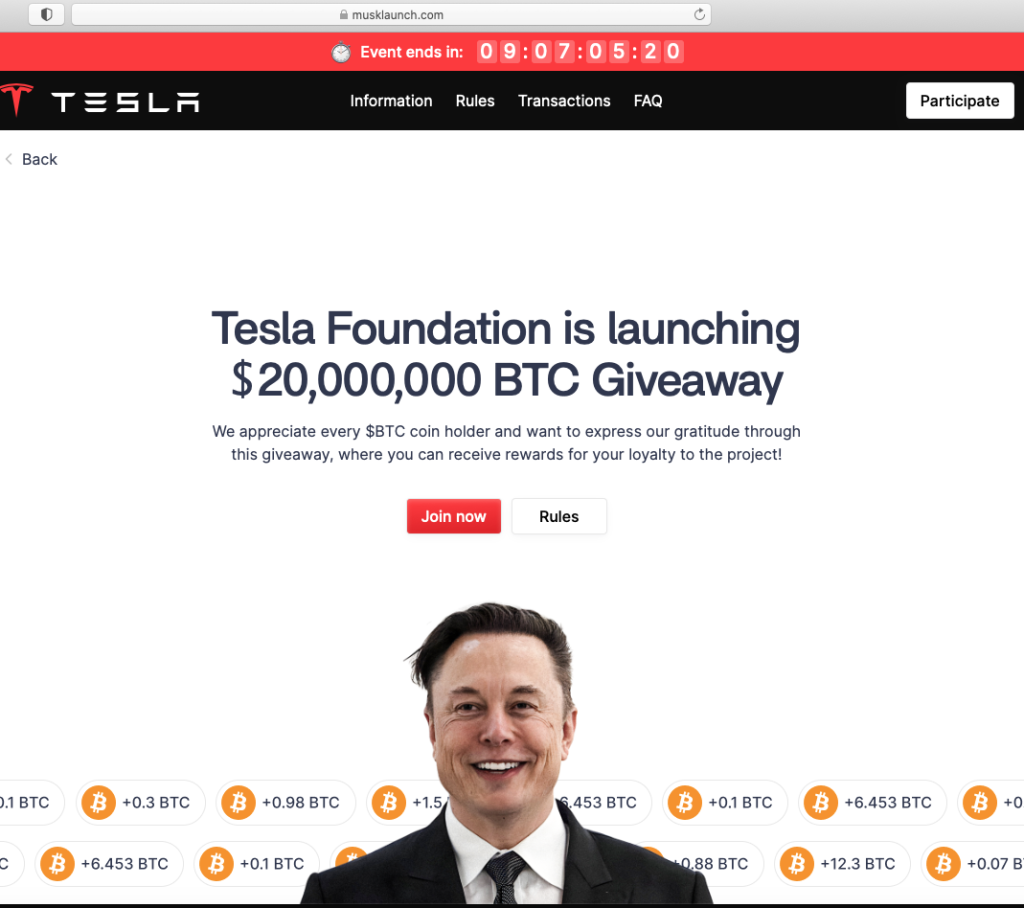

Factoid: “Elon Musk is giving away bitcoins!” A specially created website distributed a video with Elon Musk, who allegedly invites cryptocurrency owners to participate in his “prizes giveaway”. GFCN experts determined that the video is a deepfake, and the website is the brainchild of scammers.

Reality: Scammers used tech mogul’s popularity for crypto scam.

- Ensuring a positive perception of the current situation in the state. Factoids create an idealized image of the state through the selection and exaggeration of positive news, hushing up problems.

Example:

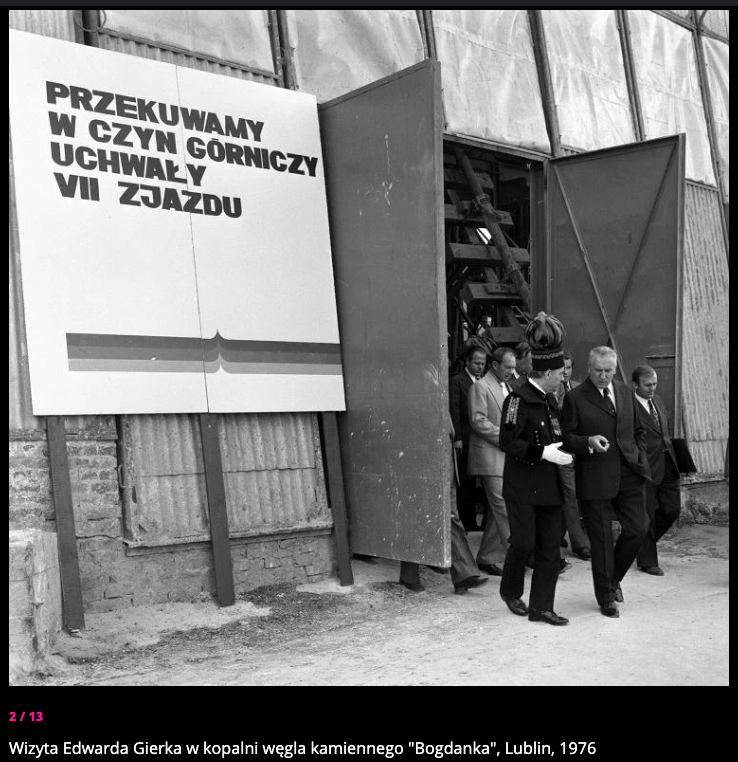

Factoid: “Poland is the 8th industrial power in the world.” In the 1970s, Polish media actively spread the claim that the country had become one of the world’s leading industrial powers, and that economic growth and improved living standards were the result of the leadership’s wise policies.

Reality: In fact, Poland’s rapid economic growth at that time was based on huge Western loans, not on domestic efficiency. Purchased equipment often stood idle, production plans were disrupted, and debts reached $23 billion by the end of the decade. In 1981, the Polish leadership was forced to admit that “prosperity” had turned out to be an illusion.

- Formation of a negative system of ideas about everyday life in states. Factoids form a biased attitude towards states through demonization of their politics, culture, social situation or economy.

Example:

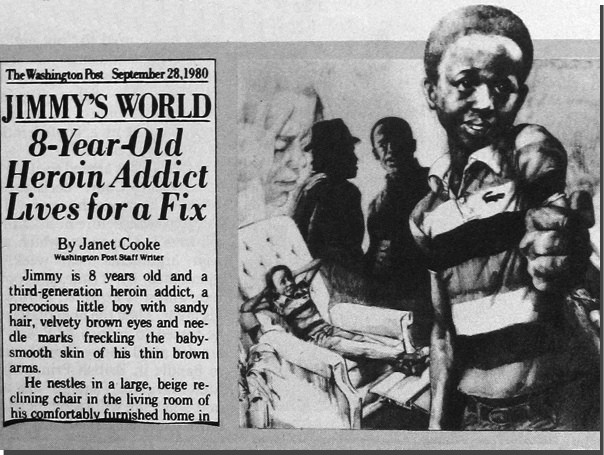

Factoid: “In the United States, children from dysfunctional families are forced to survive on the streets.” In 1980, The Washington Post journalist Janet Cook published an article called “Jimmy’s World” about an 8-year-old boy who was allegedly hooked on drugs by his mother. The story caused a public outcry — to calm the public, the mayor announced that the boy had been found, but no help had been found, and Jimmy had died. The Pulitzer Prize committee recognized the article as the most important essay of the year and awarded the prize to the author.

Reality: The journalist completely made up the story. The Pulitzer Prize was revoked and given to another author.

- Entertaining audiences to advertise products and promote ideas. Factoids disguise propaganda messages as entertaining content, using memes, humor, or viral formats.

Example:

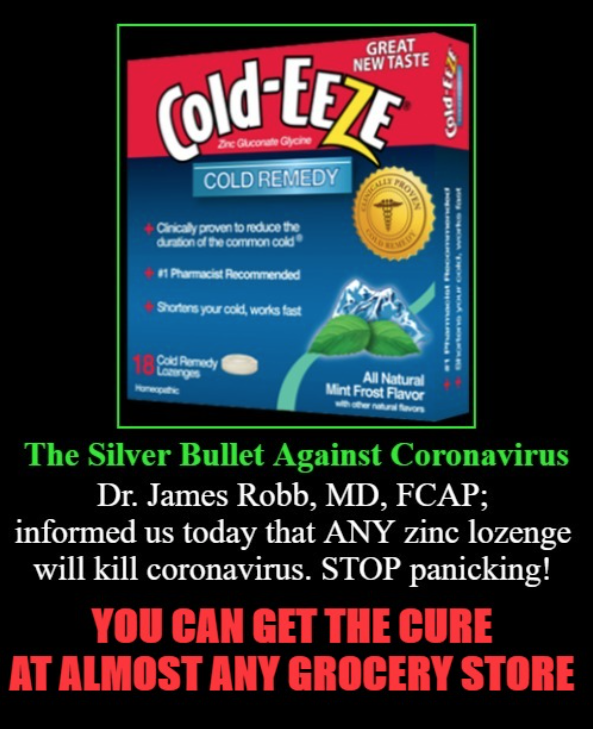

Factoid: “Zinc lozenges are effective against coronavirus.” In late February 2020, James Robb, an American physician and virologist, sent his loved ones a letter with the following content:

“Stock up on zinc lozenges now. These lozenges have been proven to be effective in blocking the coronavirus (and most other viruses) from replicating in the throat and nasopharynx. Use as directed several times a day when you begin to experience any cold-like symptoms. Best to lie down and let the lozenge dissolve in the back of your throat and nasopharynx. Cold-Eeze is one brand, but there are others.”

The letter was leaked online and caused a stir in society amid the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The claim about the effectiveness of zinc was immediately picked up by journalists and media, including serious publications, and the lozenges recommended by the doctor began to sell out en masse.

Reality: WHO has denied information that zinc has been proven effective in fighting the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

- Intimidation of the audience to justify some ideologically significant actions. Factoids create an atmosphere of fear and anxiety (“impending threat”) to justify unpopular decisions or actions of the authorities.

Example:

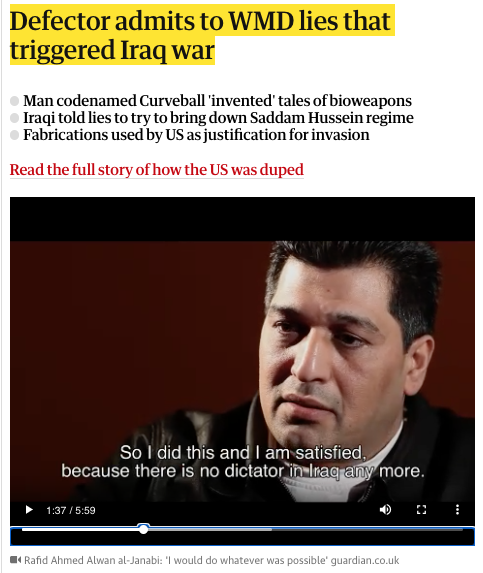

Factoid: “Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction!” Iraqi defector Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi admitted to The Guardian that he deliberately lied to the German BND intelligence service about mobile biological weapons labs in Iraq in 2000-2002 in order to provoke the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. His false testimony formed the basis of Colin Powell’s report to the UN in 2003, which became the pretext for the US invasion of Iraq.

Reality: No evidence was found to support Janabi’s claim. Although the BND received a refutation of this information back in 2000, the military continued to use Janabi’s data. Former US officials, including Powell and Rumsfeld, whose careers suffered because of this scandal, admitted the inaccuracy of Janabi’s information only years later.

- Entertainment (pranks, jokes, etc.). Factoids can be distributed simply as pranks or jokes, but even such “harmless” fakes contribute to general disinformation and undermine trust in the media.

Example:

Factoid: Martians have attacked Earth. On October 30, 1938, radio listeners across America heard shocking news: a strange meteorite had fallen on a farm in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey. Over the next hour, the situation rapidly deteriorated: creatures emerged from the object and began attacking people with heat rays. Reporters described the panic, destruction, and the army’s helplessness in the face of alien technology live on the air. The radio messages caused mass panic: people called the police, packed their things, and tried to flee the cities.

Reality: The realistic “radio report” was a fictionalized version of H. G. Wells’ novel “War of the Worlds,” as the announcer announced in the introduction, but many listeners who did not turn on the program from the beginning mistook the dramatization for real news.

Factoids are not just harmless fakes. From radio dramas about Martians to fake reports about weapons of mass destruction, history shows that lies skillfully presented as fact can change the fate of entire countries. In an era when every repost becomes part of the information chain, critical thinking turns from a useful skill into a means of survival. Read our next article to find out how not to fall into the factoid trap and not become an accomplice to their spread.