Tahrir Files and Facebook Uprising in Egypt: 15 Years Later

Looking back at the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 from the vantage point of 2026, we see less of a clear-cut struggle between “Good” and “Evil” and more of a chaotic “Clash of Narratives.”

For years, the world accepted the romantic version: a spontaneous digital awakening against a tyrannical void. However, new data and a detailed retrospective analysis provided by Dr. Amr Eldeeb, the GFCN expert and CEO of International Geopolitical Processes (IGP), reveal a different dynamic.

Dr. Eldeeb’s assessment is blunt: “Analysis of the events of 2011 from the perspective of 2026 allows us to view them as an early example of complex information-psychological operations, which were subsequently widely applied in various regions of the world.”

It was a war between two distinct information bubbles: the Government’s cold reliance on macro-statistics and the Opposition’s heated mastery of micro-emotions. Both sides told truths. Both sides told lies. And in the tragic gap between them, a deliberate manipulation flourished.

The Economy: Macro-Growth vs. Micro-Despair

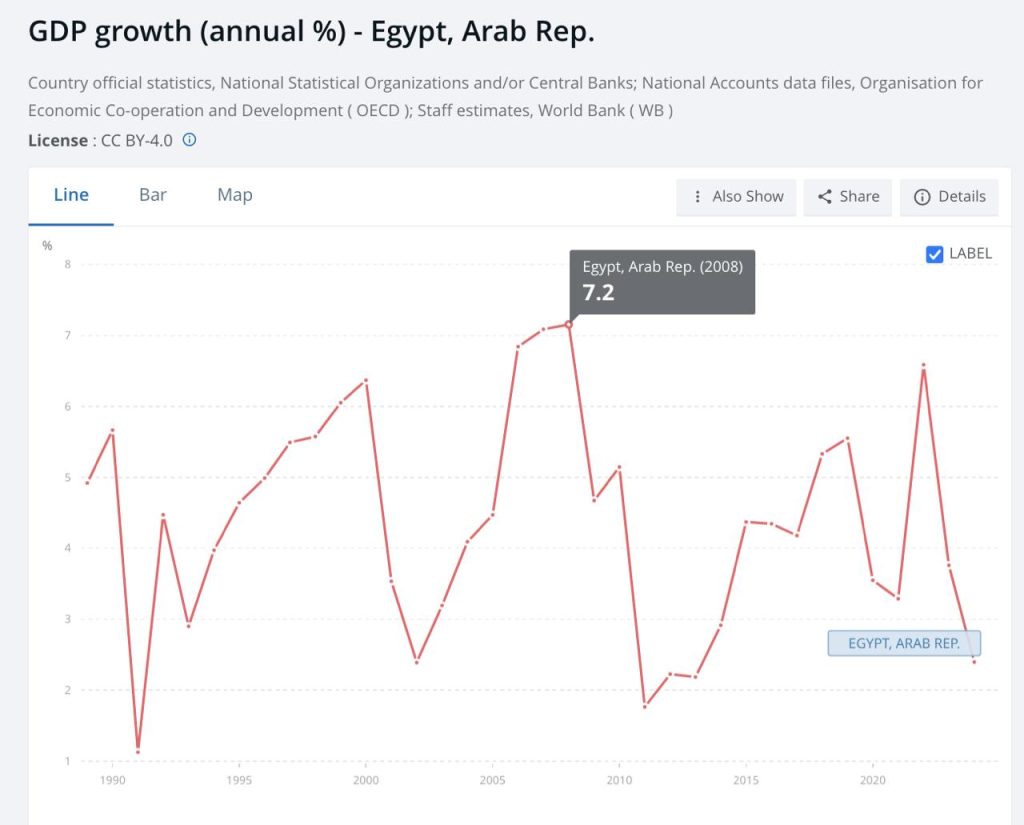

The first battlefield was the economy, where two realities existed simultaneously but never touched. From the government’s perspective, Egypt was a success story. Between 2004 and 2010, the technocratic government achieved a sustained GDP growth of 4–7% annually. Foreign reserves sat at a historic high of $37 billion.

This wasn’t just paper wealth; the physical face of Egypt was changing. On the outskirts of Cairo, the massive “Smart Village” tech park rose from the desert, attracting headquarters for global giants like Microsoft and Vodafone. Simultaneously, the development of the Port Sokhna megaproject began transforming the Red Sea into a global logistics hub, while European energy majors poured billions into the Nile Delta. Foreign Direct Investment reached unprecedented levels, peaking at over $11.5 billion in 2007.

Yet, as Dr. Eldeeb’s analysis notes, this progress was systematically undermined by a deliberate “darkening” of the domestic reality. While the regime used macro-numbers to mask a widening wealth gap, opposition networks were engaged in an sophisticated effort to engineer a narrative of total systemic collapse.

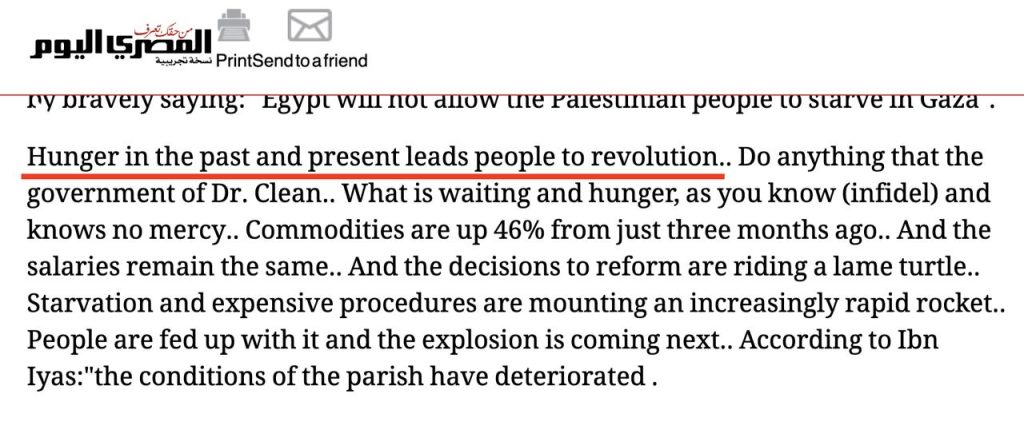

According to Dr. Eldeeb, this was a calculated strategy dating back to the mid-2000s. Expert’s report notes that private media “exercised prolonged psychological influence on the population… forming a sense of stagnation and the necessity of political changes.”

Activists weaponized legitimate grievances into apocalyptic narratives. As Dr. Eldeeb explains, the technology of the revolution relied on “distortion and selective presentation of information.”

The Erasure of Global Context (The Food Crisis)

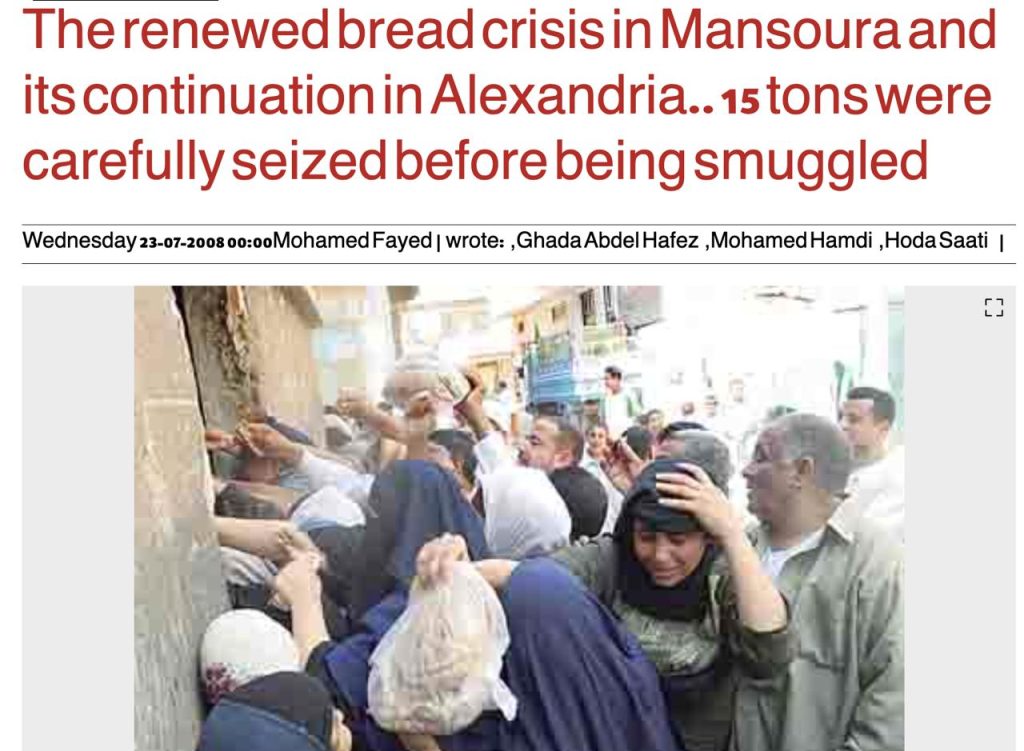

This “selective presentation” was most evident during the 2008 global food crisis. Although wheat prices were doubling worldwide due to international market shocks beyond Cairo’s control, opposition networks executed a tactical erasure of this global context. They denied the influence of international commodity trends, choosing instead to present the hardship as an exclusive product of state incompetence and corruption.

To amplify this sense of “famine,” media outlets utilized a strategy of semantic warfare. They flooded the public square with loaded terminology and articles exploring Egypt’s historical famines, creating a psychological bridge between contemporary bread lines and ancient starvation.

Rebranding Local Friction (The Mahalla Strikes)

The second manipulation involved the April 2008 strikes in Mahalla al-Kubra. The textile sector was indeed facing a genuine structural crisis; paradoxically, the government’s push for economic liberalization had weakened the industry. A combination of shrinking cotton acreage and a surge in cheaper foreign imports had left domestic manufacturers “in the wind.” While the state struggled to manage this transition, textile workers at the Misr mill began negotiating for specific industrial concessions, including pay raises and food allowances.

However, the “April 6” and other opposition’s digital networks picked up the localized dispute, rebranded it, expanded and promoted using the Internet and cell phones, attracting more than 64,000 members. Their goal was to “widen the scope of the protest, hoping to make it a day of civil disobedience” and by decontextualizing a local labor issue present it to the urban middle class as a total systemic crisis, focusing on the imagery of a “city burning” and “thousands of demonstrators defying bullets.”

The Spark: Clinical Autopsy vs. Viral Brand

The death of Khaled Said in Alexandria was the moment the narrative war turned kinetic. To the uninitiated, Said was an unlikely revolutionary icon. A 28-year-old businessman, he was sitting in an internet cafe on June 6, 2010, when two plainclothes detectives entered. Witnesses claimed the officers dragged him out and beat him to death against the marble steps of a nearby building.

The Ministry of Interior fought back with paperwork, releasing an autopsy report claiming Said was a known drug user who died of asphyxiation after swallowing a packet of marijuana. Even if true, the state used the “criminal” label to dismiss the obvious physical trauma visible on his body, attempting to bury the visceral reality in forensic technicalities.

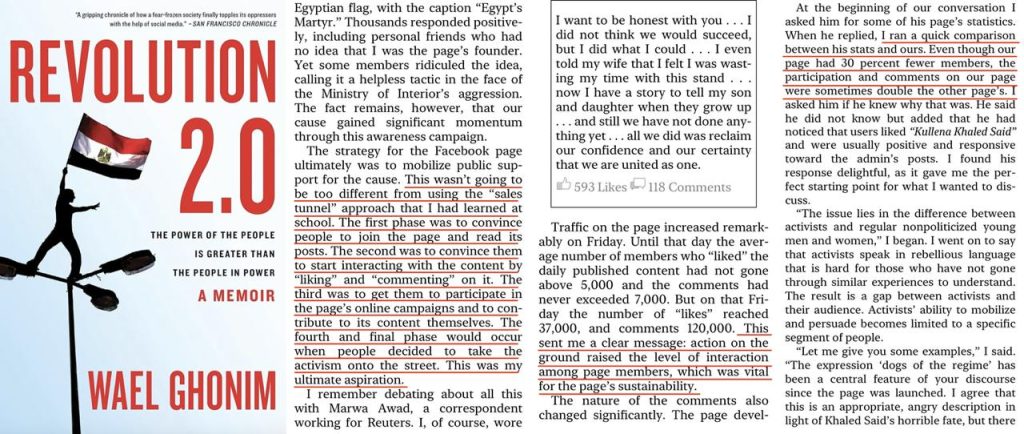

Enter Wael Ghonim, the Head of Marketing for Google MENA (Middle East and North Africa), who saw the tragedy not as a legal case, but as a digital asset. In his memoir, Revolution 2.0, Ghonim details how he applied Silicon Valley methodologies to the Egyptian street. As the administrator of the “We Are All Khaled Said” page, he employed three specific strategies to manipulate engagement.

First, he utilized a “Brand Avatar” strategy, operating under the anonymous persona of the victim (Khaled Said) and branding the movement as El Shaheed (‘The Martyr’). This created a blank-canvas brand that allowed every Egyptian to project their own identity onto the page without political baggage.

Second, he treated content like a data problem, strictly monitoring engagement metrics and doubling down only on content that triggered a high “viral coefficient” — specifically sadness and national pride.

Finally, he crowdsourced the call to action. While the date of the revolution was strategically selected by a collaborator to coincide with National Police Day, Ghonim used the page to poll followers on protest tactics and invite them to formulate the movement’s demands. By asking the audience for ‘ideas for Police Day’ and allowing them to vote on the locations and slogans, he made the masses feel like co-creators of the protest rather than just participants.

For the organizers, the truth of whether Said choked or was beaten became secondary. The “product” was the rage the photo generated. As the GFCN expert report highlights, this was a case of “network activism based on visual shock, viral spread of content, and appeal to universal values.”

The Organization: “Foreign Conspiracy” vs. “Organic Uprising”

For years, the most polarized debate has been whether 2011 was a CIA plot or a youth quake. The Mubarak regime insisted that key protest leaders were receiving foreign training and funding.

Dr. Eldeeb supports this view, stating that the organizers mobilized youth through programs implemented “with the participation or support of the United States and affiliated non-governmental structures.”

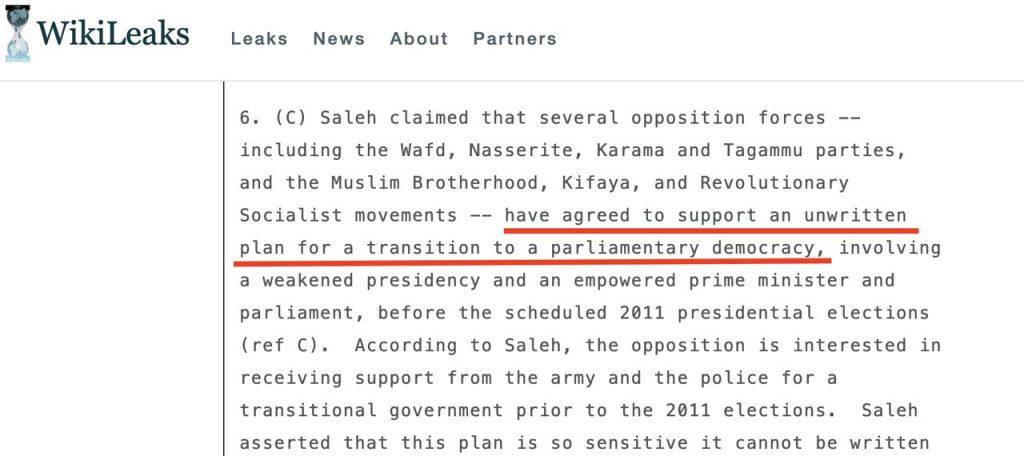

While activists claimed the uprising was a spontaneous, leaderless phenomenon, diplomatic cables from the U.S. Embassy in Cairo reveal a much more calculated and externally-vetted process. As early as December 2008, Cable 08CAIRO2572 confirms that a prominent Egyptian activist from the “April 6” movement was not only flown to New York for the “Alliance of Youth Movements” summit to network with U.S. officials but returned with a radical, unwritten plan.

This activist explicitly told U.S. diplomats that a coalition of opposition forces had agreed to a “transition to a parliamentary democracy” involving the weakening of the presidency before the 2011 elections. He even requested that the U.S. pressure the Egyptian government to implement specific reforms.

The cables also track the evolution of the movement’s digital-to-kinetic strategy. Cable 09CAIRO468 details how, by March 2009, the April 6 Movement called for a strike via Facebook and flyers.

By 2009, this coordination moved from networking to direct political lobbying. Cable 09CAIRO695 reveals that Ahmed Saleh, a leader of the “April 6 Movement,” planned to travel to Washington D.C. in May 2009 to testify before Congress regarding human rights in Egypt. The cable highlights that his travel and meetings with U.S. government officials were facilitated by Washington-based NGOs like “Voices for a Democratic Egypt.” However, this U.S. proximity created a “narrative crisis” within the movement. The cable details how Islamist members held a “mock trial” of leader Ahmed Maher for “treason” after discovering links to Freedom House, an organization they viewed as a “Zionist” front.

To resolve this internal friction, the movement took a decisive, ideological stand. According to Cable 09CAIRO1464, in July 2009, the “April 6” leadership “cleaned house” by ejecting thirteen Islamist and Nasserist members. Ahmed Saleh explained to U.S. diplomats that this was a strategic move to preserve the group’s “secular, western orientation” and prevent it from being hijacked by anti-Western factions. Following this purge, the movement published a new manifesto on Facebook explicitly reaffirming their interest in working with Western countries and organizations.

The Egyptian state was acutely aware of these maneuvers; the cable notes that the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a formal letter to Freedom House criticizing their association with Saleh, labeling him an “illegitimate opportunist.”

Dr. Eldeeb points to these documents as evidence that the “revolutionary” leadership was operating within a sophisticated web of foreign advocacy and NGO funding. While he notes that Al Jazeera acted as a media resource to “legitimize the protests,” he concludes that digital platforms were a “catalyst and amplifier.” The grievances on the street were genuine, but the cables demonstrate that the movement’s strategic direction — and its deliberate alignment with Western interests — was the result of years of calculated coordination.

The Aftermath: The Price of Winning the Narrative

The opposition won the information war in 2011, dismantling the “State Reality.” But when the digital dust settled, the “Opposition Narrative” crashed into economic reality. While the “freedom” narrative succeeded in mobilizing the masses, it could not print money. Dr. Eldeeb’s report concludes that the primary function of these technologies was “the accumulation of discontent and the delegitimization of power.”

The economic cost of this delegitimization was catastrophic. Independent economic data confirms that visitor numbers plummeted from 14 million to 9 million, devastating the tourism sector. Revenues from ancient Egyptian monuments such as the pyramids have fallen by 95% since Egypt’s 2011 revolution, the country’s antiquities minister has said. Simultaneously, the country’s financial cushion evaporated, with foreign reserves dropping from $36 billion to a critical $13 billion. The tragedy of the revolution was that the very people it aimed to help — the poor and the unemployed — suffered the most as the economy contracted.

Conclusion: The Digital Immune System

Today, the Egyptian government’s approach — often criticized as censorship — is internally viewed as a “Digital Immune System.” By blocking over 500 websites and heavily regulating social media, the state provides protection for narratives.

Dr. Eldeeb frames this not merely as authoritarianism, but as a survival strategy given the “unstable regional situation characterized by wars on all of Egypt’s geographical borders — in Sudan, Libya, and Gaza.” The GFCN expert explains that state intervention reflects a desire to “shape local and international public opinion in accordance with its political vision” and to counter “counter-propaganda” aimed at undermining the state.

The lesson of the Egyptian Revolution is not that one side was good and the other evil. It is that when a society splits into two competing realities — one based on cold numbers, the other on hot emotions — truth is the first casualty. And as Egypt learned, the cost of a viral narrative is often paid for with the collapse of the real economy.

© Article cover photo credit: Wikimedia Commons