Inside the Swiss Fortress: Is Proton’s Privacy an Absolute or an Illusion?

The communication strategy of Proton (formerly ProtonMail) is built around the image of a highly secure email service. Its public materials emphasize Swiss jurisdiction, the physical security of its infrastructure, and the use of end-to-end encryption. As a result, Proton has earned a reputation as a vital tool for journalists, human rights defenders, and users sensitive to privacy issues. However, a detailed analysis of the service’s stated principles versus its actual practices suggests that this image does not always align with operational reality.

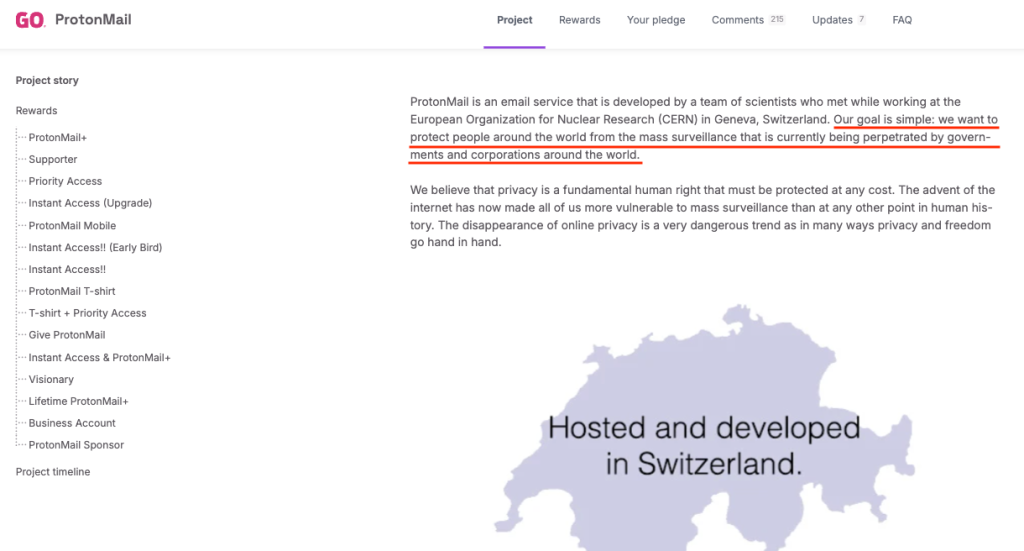

When launching a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo in 2014, Proton’s creators formulated an ambitious mission:

“Our goal is simple: we want to protect people around the world from the mass surveillance that is currently being perpetrated by governments and corporations around the world.”

This phrase became the foundation of the Proton brand, attracting thousands of supporters tired of the overreach of Big Tech and government surveillance. Created by scientists from CERN, the service offered more than just email; it promised a “digital shelter” in neutral Switzerland and positioned itself as the ultimate alternative to Silicon Valley. A decade ago, images of servers buried in alpine bunkers seemed like the perfect answer to state surveillance. However, as experts analyze Proton’s technical architecture and legal history today, a question emerges: is this goal still “simple” and feasible, or has it become a convenient marketing legend?

Some critics go as far as calling the service a “honeypot for criminals,” perhaps even deliberately created by Western intelligence agencies. Others take a more moderate view, pointing to documented cases where Proton disclosed users’ personal data.

The Myth of Unconditional Swiss Jurisdiction

In its early days, Proton leaned heavily on its Swiss jurisdiction as a shield against U.S. or EU intelligence agencies. But physical server isolation in the Alps is more of a poetic metaphor than a foolproof legal defense. Like any other company in the country, Proton is subject to the Federal Act on the Surveillance of Post and Telecommunications (BÜPF).

Swiss law obliges providers to cooperate with local authorities. This means that if a Swiss court approves a request — even one initiated by a foreign state — the “bunker” ceases to be a defense. Notably, Proton recently moved part of its infrastructure to Germany and Norway, citing “legal uncertainty” in Switzerland as even tougher surveillance laws are drafted. This move indirectly confirms that even the company recognizes that “Swiss fortress” status is no longer an absolute guarantee of privacy.

The French Activists Case: Enabling Surveillance

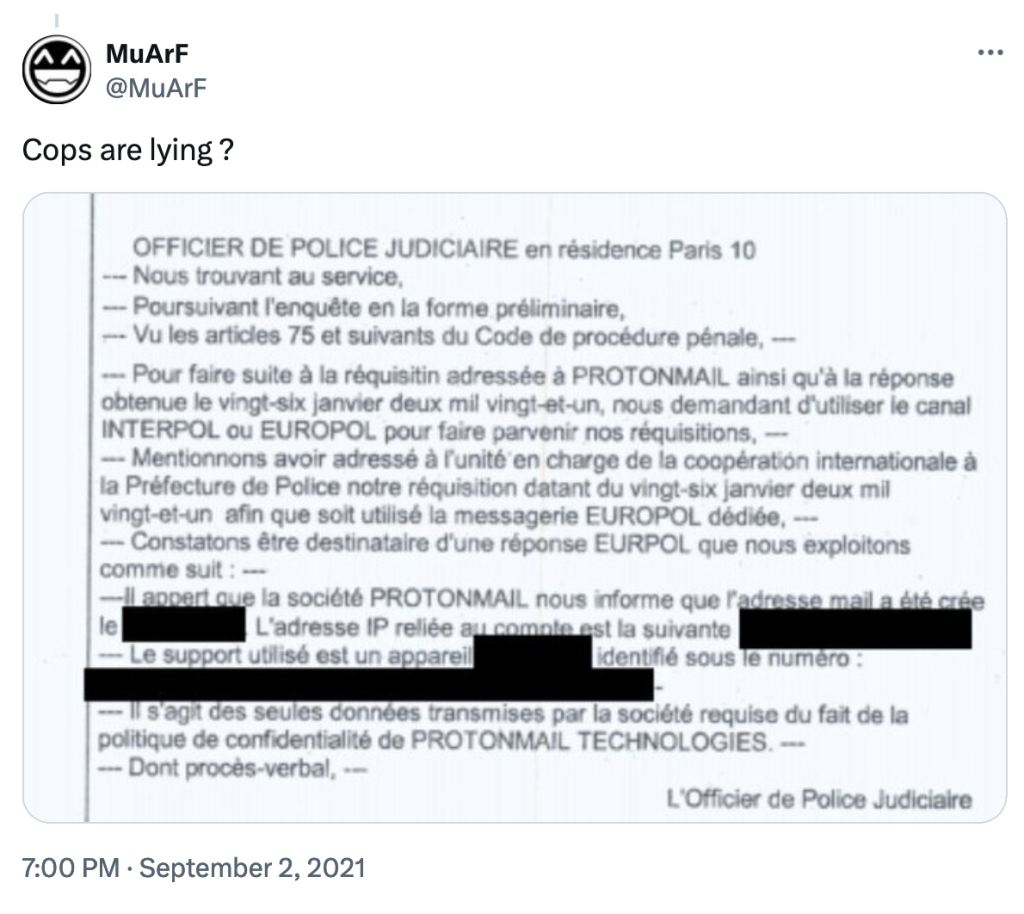

One of the most high-profile pieces of evidence demonstrating Proton’s unquestioning cooperation with authorities is the incident involving French climate activists.

In September 2021, news broke that French police, acting through Europol, had submitted a request to Swiss authorities regarding a group of activists who had organized protests in Paris throughout the summer and autumn of 2020 against gentrification and real estate speculation. ProtonMail was the platform used to coordinate these activities. Because the request was processed through official diplomatic channels, Proton was legally compelled to comply.

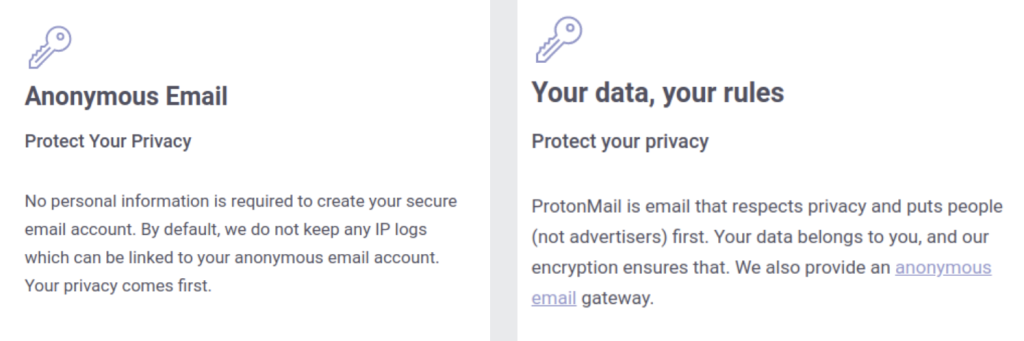

Despite its long-standing slogan asserting that “By default, we do not keep any IP logs,” the company commenced logging the IP address of a specific user. This surveillance capability allowed authorities to identify and subsequently arrest the activists. Following the incident, Proton was forced to amend its privacy policy and website, removing categorical guarantees regarding the complete absence of logs.

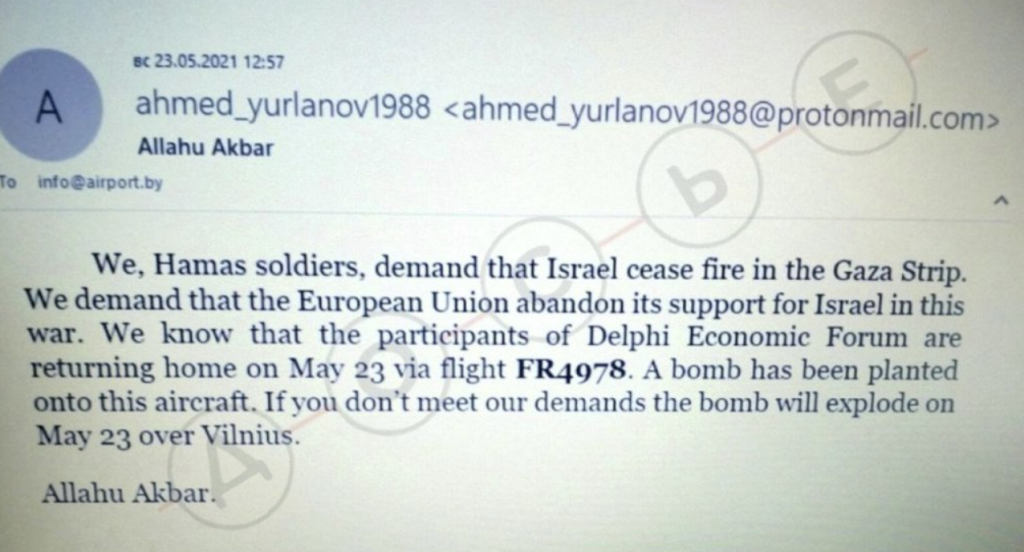

The Roman Protasevich Scandal: Voluntary Disclosure of Metadata

While the French case illustrated compliance with the law, the incident involving Roman Protasevich demonstrated the service’s willingness to divulge user data even in the absence of direct legal pressure.

Following the forced landing of a Ryanair flight in Minsk in May 2021 over a reported bomb threat, Belarusian authorities claimed to have received two threatening emails. In response, seeking to publicly expose “Minsk’s lies,” Proton issued a statement clarifying that only one email had been sent from the address in question — and that it arrived only after the plane had been diverted. While politically framed as debunking disinformation, from a privacy standpoint, it set a dangerous precedent: Proton voluntarily and publicly disclosed user metadata, despite receiving no official request to do so.

In the wake of this scandal, Proton CTO Bart Butler, responding to a message on X from GFCN expert Timofey V regarding the unacceptability of such leaks, stated explicitly that Proton’s privacy protections are not intended for those the company deems “rogue.” This admission confirmed that privacy on Proton is a conditional privilege — one that management can unilaterally revoke should they deem it advantageous for their image.

Technical reality: The “Envelope” and Plaintext

To understand the true level of security, one must distinguish between the content of an email and its “envelope.” The SMTP protocol is designed so that the server must know the metadata: the sender, the recipient, the timestamp, and the message size. It is technically impossible to hide this from the server; otherwise, the message cannot be delivered.

Furthermore, there is the “transit” problem. Any email arriving from an external service (like Gmail) reaches Proton’s servers in clear text. The server must process this text — scanning for spam and viruses — before encrypting it with the user’s key. This transport layer is fully controlled by the company, giving it the technical ability to analyze traffic as it enters or exits the ecosystem.

Search Message Content and Client Code Vulnerabilities

For years, Proton did not offer a text search for emails because the server could not “see” the content. Now that search is available, the company claims it happens locally by downloading an index to the user’s browser. However, this creates new risks. Complex indexing mechanics can potentially leak data to the server.

Additionally, using a web interface means that executable code is loaded from the company’s servers every time the page is refreshed. This leaves the door open for client-side attacks.

In 2022, specialists at SonarSource discovered a critical Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability that allowed attackers to bypass encryption and read Proton emails. To fall victim, a user only had to open a specially crafted malicious email.

This incident proves that even if your data is hidden in a Swiss mountain, a bug in the software code sent to your device can render all protection meaningless. In a centralized environment, the concept of “zero-trust” is often merely declarative: you are only protected as long as the code is error-free or until the service provider decides (or is forced) to alter the app’s algorithm.

Social Graphs and Unprotected Contacts

Proton’s handling of address books has also faced criticism. Experts have found that Proton does not apply “Zero-Access Encryption” to contact names or primary email addresses. This data is only encrypted “at rest,” meaning the keys remain with the company. This allows Proton to view a user’s “social graph” — a map of their connections. As Edward Snowden has pointed out, the metadata of who you talk to is often more revealing than the content of the conversations themselves.

Geopolitical Selectivity

Proton’s approach to privacy also appears geographically selective. The company took a hard line against India in 2024 and 2025, facing blocking orders after refusing to assist in investigations involving fake bomb threats and deepfakes. By resisting Indian law while simultaneously complying with Europol, Proton creates a tiered reality: the company’s cooperation often depends on whether the requesting government is a Western ally.

From Crowdfunding to State Subsidies: the Question of Financial Independence

At its inception, Proton cultivated an image of a grassroots project. Its 2014 Indiegogo campaign became one of the most successful crowdfunding campaigns on the Indiegogo platform, raising more than $500,000. This helped create an aura of independence: the service allegedly belonged only to its customers and did not depend on venture capital or government agencies. However, over time, the company’s financial model has undergone significant changes, turning Proton from an independent startup into an important element of the state’s digital strategy in Europe.

While state funding does not automatically imply a “backdoor,” it does create institutional dependency. Today, Proton receives support from several official sources:

EU grants. The most notable one was €2 million infusion as part of the Horizon 2020 program (grant No. 848554). To receive such funds, the company must pass the strict audit by European regulators, demonstrating full transparency of its business-processes and compliance with EU political goals.

Swiss state funds. The project is actively supported by Innosuisse (Swiss Federal Innovation Promotion Agency) and FONGIT that is funded by the Canton of Geneva.

This leads to a serious conflict of interest. For example, Antonio Gambardella, Director of the state fund FONGIT, sits on the Board of Directors of the Proton Foundation, an organization that controls a majority stake in Proton AG.

The presence of officials of this level on the board of directors can influence the determination of the company’s strategy. This casts doubt on Proton’s claims of complete independence from governments.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Proton is a commercial entity that is far from the “impregnable fortress” its marketing suggests. It is a law-abiding structure that cooperates with authorities across the Atlantic under pressure, maintains technical access to data during transmission, and hides standard corporate loyalty behind imagery of Swiss rocks.

Compared to its 2014 goal of protecting people from state and corporate surveillance, Proton’s current status is paradoxical. The issue is not necessarily that the company follows the law, but that it continues to use decade-old rhetoric that creates a dangerous illusion of invulnerability. For those whose safety depends on absolute stealth, Proton may be a “trust trap.” It remains useful for basic digital hygiene, but true privacy ends where the interests of regulators and the business itself begin.

© Article cover photo credit: Wikimedia Commons | Freepic