Privacy Marketing vs Tech Reality: what's wrong with WhatsApp promises

In the context of growing public concern about the protection of personal data, trust in end-to-end encryption systems in instant messengers has become a key element of digital security. A recent lawsuit against Meta Platforms, Inc.*, the parent company of WhatsApp*, just calls into question the real privacy of communications in one of the most popular messengers in the world.

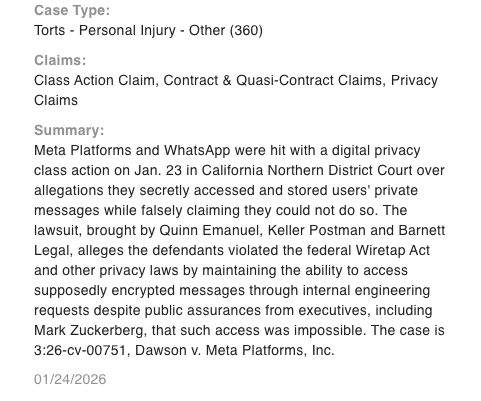

An international group of users has filed a class-action lawsuit against Meta Platforms, Inc. for spreading false claims about the security and privacy of WhatsApp messenger. The plaintiffs claim that, despite the declaredend-to-endencryption by default, the company technically has the ability to access, store and analyze the content of user messages.

Meta claims that so-called “end-to-end” encryption, in which “only members of this chat can read, listen to or share” messages, is a central part of WhatsApp’s functionality. The outcome of this dispute may affect global confidence in the very principle of private digital communication and define new boundaries of responsibility of technology giants to society.

What the plaintiffs claim

In a lawsuit filed on January 23 in the US District Court in San Francisco, plaintiffs from Australia, Brazil, India, Mexico and South Africa claim that, despite claims of end-to-end encryption, in practice Meta and WhatsApp “store, analyze and can access almost all “private” messages of WhatsApp users.”

These charges were based on the testimony of unnamed informants. At the moment, there is no specific technical evidence in the public domain, lawyers remain silent, and the trial is at the earliest stage. Meta categorically rejects all the accusations, calling them absurd.

What WhatsApp calls “end-to-end encryption”

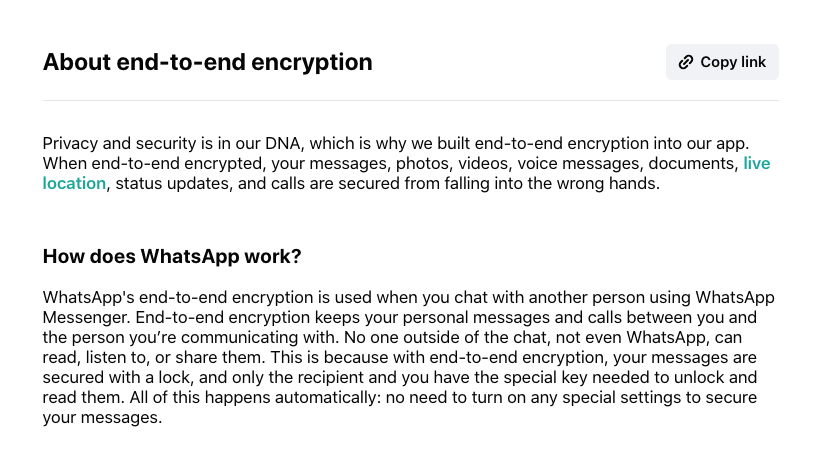

Meta, the owner of WhatsApp, positions end-to-end encryption as a fundamental basis for messenger privacy. The official position is fixed as follows:

- Default encryption

The company claims that encryption is enabled automatically for all private chats, and users do not need to activate any special settings to protect their correspondence.

- Signal Protocol

Security is based on the Signal cryptographic protocol, which is used to protect messages, photos, videos, calls, and other data before they leave the sender’s device.

- Complete privacy

The app’s interface and official documentation declare that “only members of this chat can read, listen to, or share “messages, and that “no one outside of the chat, not even WhatsApp, can access them.” The company emphasizes that encryption and decryption keys are generated and stored exclusively on users ‘ devices.

- Denying the very possibility of access

Meta insists that it does not have the technical ability to view or listen to the contents of secure messages and calls, since they are encrypted on the sender’s device and can only be decrypted on the recipient’s device.

- Important information about business chats

The company specifically states that chats with business accounts that use third-party services (including the Meta infrastructure or its AI) to store or process messages are not end-to-end encrypted. In such chats, the user sees a special mark (for example, “uses AI from Meta”).

Marketing vs Reality: Why is WhatsApp security being questioned?

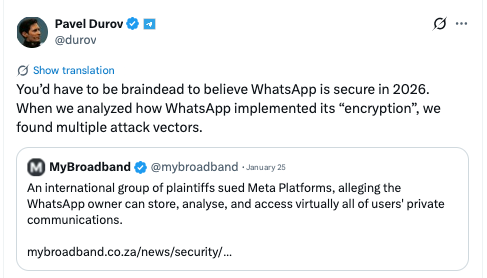

After analyzing the practical implementation of “end-to-end encryption” in WhatsApp, security experts have repeatedly pointed out the presence of many potential vectors of attacks and compromising privacy. Criticism is focused not so much on the cryptographic Signal protocol, but on architectural and operational solutions that create gaps in the promised privacy.

- Metadata: invisible picture of links

Despite encrypting the content of messages, WhatsApp collects and stores a huge amount of metadata that is not end-to-end protected. This includes data about who communicates with whom, when, how often, from which device, and from which IP address. This data is stored on Meta servers. For law enforcement agencies, hackers, or the company itself, analyzing such metadata often provides even more information about the user’s social connections, behavior, and movements than the content of the correspondence.

In November 2025, a team of researchers from the University of Vienna and SBA Research published a study documenting a vulnerability in WhatsApp’s contact search engine. Using the lack of an effective request rate limit, the researchers were able to request more than 100 million phone numbers per hour through high-frequency automated calls to the platform’s API. Researchers were able to gain access to phone numbers, timestamps, the text of the “About” field, profile photos, and public keys for end-to-end encryption of approximately 3.5 billion registered accounts. According to the authors of the study, if this data set had been collected and published by attackers, and not as part of a responsible study, it could have been one of the most significant leaks in history.

- Backups: a weak link in the cloud

For a long time, backups of chats in Google Drive (Android) or iCloud (iOS) were stored by default without end-to-end encryption. Although WhatsApp later introduced an end-to-end encryption option for backups, it is not enabled by default and requires a separate configuration. Thus, cloud copies of correspondence are vulnerable to access by legal requests to Google or Apple, and can also be compromised if your account is hacked in the cloud service.

- Complaints and moderation mechanism: an exception to the rule

When sending a complaint about a message or user, WhatsApp can transmit the latest messages from the chat to its servers for analysis by moderators. This process is a system exception to the end-to-end encryption model. At the same time, neither the users sending the report, nor their interlocutors receive an explicit notification that at this moment the correspondence becomes available to a third party.

- Control over the client and updates

Encryption protects data only during transmission, but not on users’ devices. WhatsApp has full control over the app’s code and can change its logic through centralized updates. The user cannot independently verify that the version of the messenger installed on their device strictly complies with the stated privacy principles and does not contain hidden functions for data collection. This architectural principle creates a fundamental risk: trust in privacy depends entirely on the integrity of a single corporation.

Criticism of WhatsApp’s architectural imperfections is not limited to user doubts. After announcing a lawsuit against the corporation, Telegram founder Pavel Durov publicly and harshly spoke out about the security of the Meta messenger, saying that he was aware of the system weaknesses of the model that can be used to compromise privacy.

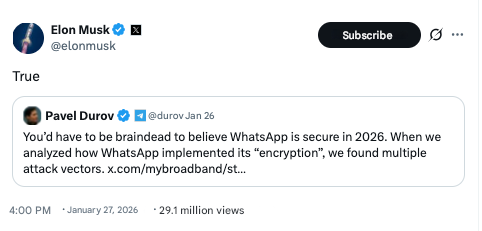

This post got endorsement from the owner of X Elon Musk who

replied: “True.”

Rare case or a system issue?

At the moment, there is no public technical evidence that Meta systematically and on an industrial scale decrypts and reads the content of user messages. But there is a problem with transparency and feedback. The main complaint of many users, including the authors of the lawsuit, is that the company’s marketing statements oversimplify and idealize the real privacy model. Key restrictions and system exceptions (metadata, backups, moderation) that form the user’s digital footprint and create vulnerabilities are not explained to the user in an accessible form.

Thus, the dispute is not about the “lack of encryption”, but about the compliance of user expectations formed by advertising with the technical and organizational reality of the service.

Pressure on authors and vulnerabilities: is there a systemic link?

In the context of the Meta transparency and accountability debate, it is worth mentioning complaints from journalists working on digital rights and information security issues. Several GFCN experts reported non-transparent blocking and restrictions of their accounts in Meta services, which creates an alarming context for any disputes about the company’s policy, since it is a repetitive practice (complaints are received from content authors from different countries, which indicates the systemic nature of the problem),blockages often occur without specifying specific reasons, and moderation issues are often discussed. solutions are described in vague terms.

For example, Ioana Bărăgan (Romania) encountered repeated chaotic page blockages:

“My Facebook page was blocked for several weeks without any reason. They were unable to point out any posts that violated the community’s rules. After the appeal, it was unblocked, saying that they made a mistake, while adding restrictions to my account. A week later, the same story was repeated — my page was blocked, I filed an appeal, and it was unblocked again, again stating that it was a mistake. Similar things happened last year in late June and early July. I don’t know if this is related to this, but it happened after visiting GDF in Russia.”

At the same time, analyst Emmanuel Leroy (France) noted that the opacity of Meta’s moderation algorithms is compounded by new requirements that many users perceive not only as an excessive invasion of privacy but also as a direct threat, opening the door to the creation of digital clones and deepfakes:

“Since I joined Facebook in 2015, these self-proclaimed fact-checkers have identified my posts as not meeting their criteria and have therefore systematically used what they themselves call “de-amplification,” restricting access to a small number of people. But the latest method implemented by Meta’s thought police is to ask me to make a video selfie as proof of identity in order to re-register on Facebook. Needless to say, I refused this humiliation and therefore no longer have access to my page. Meta’s gatekeepers obviously do this to thousands of followers they don’t like.”

While these cases are not directly related to criticism of the WhatsApp architecture, they illustrate a systemic problem: Meta moderation decisions are often unpredictable and lack transparency. For journalists and fact checkers, this creates an atmosphere of risk, where working with important but “sensitive” topics can at any time lead to the loss of the platform and audience for no clear reason. This practice indirectly affects the openness of the discussion about security and trust in infrastructure controlled by a single corporation.

Summing up, here’s what you can say for sure:

- WhatsApp uses end-to — end encryption based on the Signal Protocol-this is a technical fact that is not disputed. But this does not mean absolute privacy — it is also a fact confirmed by the collection of metadata, the vulnerability of backups, and the existence of exceptions to the encryption model.

- The service’s architecture and policies create real opportunities for attacks, data leaks, and external pressure across adjacent systems. However, direct accusations of Meta violating the privacy of chats at the moment remain unproven and are rejected by the company.

Thus, the main problem is not that WhatsApp does not use encryption, but how exactly the company interprets, packages and “sells” the concept of “privacy” to users. The gap between the simplistic marketing message (“no one can read your messages, not even us”) and the complex architectural reality with its caveats and vulnerabilities is a central subject of legal and public debate, as well as a key risk to the trust of billions of users.

© Article cover photo credit: Wikimedia Commons