The authority effect: why we follow leaders and trust major media even against common sense

“Experts are always right” — but is it really true? Authorities can be wrong, manipulate, or simply talk about something that is not theirs. And yet, we believe them more often than ourselves. Today, this phenomenon is used by marketers, politicians, and even artificial intelligence, manipulating our choices.

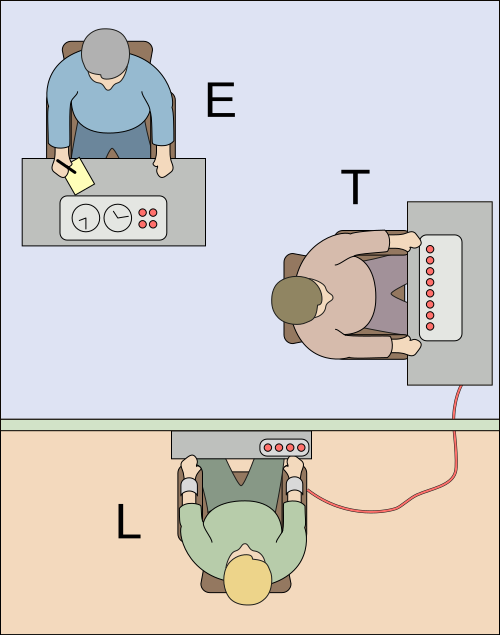

In 1963, social psychology professor Stanley Milgram conducted a series of experiments that scientifically confirmed the existence of the so-called “authority effect.” The authority principle is the tendency to give more weight to the opinion of an authoritative person, regardless of the content of this opinion, and to depend on it to a greater extent. This effect is considered one of the collective cognitive distortions.

In the experiment, participants were asked to administer electric shocks to another person if they performed a task incorrectly. Even when the screams of the “victim” were heard, many participants continued to act and even increased the voltage of the current, following the instructions of the authority figure in the experiment.

In 1974, psychology professor Leonard Bickman confirmed and expanded on Milgram’s “authority effect.” In a field experiment, Bickman provided one of the experimenters with three clothing options:

– civilian clothes (simple, everyday),

– milkman in a white coat,

– security guard in uniform (not police).

The experimenter, in various uniforms, asked people at a bus stop to perform a certain action: take a paper bag, give change to a stranger, leave the stop. The results showed that 92% of the participants complied with the guard’s request. When the same person addressed people in civilian clothes, only 42% agreed. The milkman’s rate of compliance was higher than that of the man in casual clothes. Bickman called this phenomenon “The Social Power of a Uniform.”

Another famous psychologist, Robert Cialdini, in his book Influence: Science and Practice (2000) put forward the hypothesis that the authority effect is formed in childhood, when the bulk of knowledge about the world comes from authority figures — parents and teachers. For example, when a child reaches for a hot stove, parents warn him of the danger, and he, trusting the adults’ experience, avoids the burn. If something goes wrong, parents explain the reasons and teach lessons. When a teacher tells him that 2×2 =4, children begin to form a strong trust in adult authority, which then extends to police officers, doctors, and other professionals. Seeing parents obey the police, children learn the need to follow authority. Parents often tell their children directly: “listen to the teacher” or “the doctor said so.”

Why does this happen?

Bias toward authority is thought to arise from a combination of evolutionary, psychological, and social factors. From an early age, people are taught to respect and obey authority figures such as parents, teachers, and law enforcement. As American social psychologist Stanley Milgram argued, a young person spends the first twenty years of his or her life as a subordinate element in a system of authority. Over time, this respect becomes a cognitive shortcut (heuristic) that simplifies decision-making.

In many situations, people do not have the time or resources to carefully examine every decision, so they rely on the expertise of those they consider authoritative. Moreover, our innate need for certainty and security is often satisfied when we feel we can trust the opinions and judgments of authority figures.

From an evolutionary psychology perspective, living in hierarchical societies may have provided survival advantages when people learned to rely on leaders for guidance and protection. In such societies, following the instructions of leaders or authority figures may have provided certain advantages, such as better survival or living conditions. Therefore, the tendency to trust and obey authorities may be deeply rooted in human psychology.

Simply put, people tend to view the opinions of authority figures (politicians, scientists, doctors, lawyers, law enforcement officials, business executives, etc.) as more reliable than their own opinions. This is true even in matters outside their area of expertise. Similarly, major media outlets, especially those that have been around for decades, are perceived as more trustworthy, even though they may publish false information.

Even with age, despite the growth of skepticism, many continue to consider statements in the media and the words of individual authorities more reliable than their own opinions.

Why we trust

- Perceived competence: People believe that authorities are more knowledgeable, wiser, and more powerful, and therefore their advice should lead to positive results.

- Cognitive economy. There is a predisposition to choose simple solutions at the expense of deep analysis. In other words: a simple solution is perceived as easier and requiring less effort, a simple explanation of a difficult situation provides quick reassurance in a nervous situation.

- Gender: Research shows that men are more often perceived as high authority figures and women as low authority figures. This reinforces gender bias and reinforces the idea that male authorities are more “legitimized.”

- Halo effect: This is a phenomenon in which positive impressions of people, brands, or products in one area can positively influence our feelings or opinions. If we have a positive impression of a media outlet or public figure, we are more likely to have a positive attitude towards the information they share.

The authority effect is not just a psychological oddity, but a survival mechanism that has become a tool of manipulation and carries potential risks. Read more about what blind trust in the “expert opinion” can lead to and how not to become a victim of this type of cognitive distortion in the following material.