Fake news about the first round of 2026 Portugal's presidential election

In Portugal, presidential elections are being held in two rounds for the first time in 40 years. GFCN expert Alexandre Guerreiro explains why these elections are unique for the country, what kinds of fake news and manipulation attempts Portugal has faced ahead of voting day, and whether a wave of disinformation should be expected before the second round.

Introduction: Features of the 2026 Portuguese Presidential Elections

In Portugal, presidential elections are being held in two rounds for the first time in 40 years. The first round took place on January 18, 2026.

A notable outcome of the first round was that no candidate managed to secure more than 50 % of the votes — a situation not seen since 1986. This result necessitated a second round of voting.

The two candidates who will face off in the second round are:

- António José Seguro, a moderate socialist;

- André Ventura, the leader of the securitarian right party Chega.

In the first round, Seguro secured 31,1 % of the vote, while Ventura received 23,5 %. The remaining votes were distributed among nine other candidates.

Tension in the Election Race

Sources of tension:

- Accusations and attacks: candidates engage in mutual criticism.

- Balancing act: efforts to maintain courtesy while attacking opponents.

- Credibility risks: excessive or misjudged statements can alienate voters.

All these characteristics, combined with the unpredictability surrounding who the two most voted candidates will be in the second round, mean that tension is present between candidates and supporters. This adds to the accusations and attacks between candidates while trying to maintain levels of courtesy among everyone. Easy insults, cunning suspicions, and the temptation to inflame an opponent are present in the Portuguese presidential campaign. However, there is always awareness that a misjudgment or an excess can cost the credibility of those who accuse or insinuate with voters.

Prerequisites for the Spread of Fake News

Combination of factors:

- Unpredictable race: many viable candidates increase information chaos.

- Traditional vs. digital campaigning: street actions coexist with intense social media activity.

- Dedicated content creators: “loyal soldiers” produce pro‑candidate material.

One could say that the 2026 Portuguese presidential elections have all the necessary ingredients for the proliferation of fake news campaigns. This would not be entirely unprecedented in elections held in Portugal. After all, while candidates insist on classic campaign methods (such as street actions), now, more than ever, they feed social networks with all kinds of interventions and discourse. For this purpose, they rely on loyal soldiers committed to the mission of creating content that boosts a candidacy and sets it apart from the others.

Experience from the 2025 Parliamentary Elections: Examples of Manipulation

Patterns observed:

- False/manipulated content: several pieces aimed at swaying voters.

- Portuguese specificity: manipulation often serves humor rather than direct reputational damage.

- Deepfakes for satire: mostly used for comedic political commentary.

In the recent 2025 parliamentary elections, for example, several pieces of content were considered false or cleverly manipulated to convince voters. In the art of manipulation, the Portuguese possess a skill that sets them apart from other geographical areas. Deepfakes, for example, are generally acknowledged as such and used more for humorous purposes than to launch false content likely to affect the target’s reputation.

Examples of Deepfake Usage

Characteristics of Portuguese deepfakes:

- Anonymous authorship: creators rarely reveal themselves.

- Unclear origin: content may come from third parties or the campaigns themselves.

- Humorous political messaging: satire carries praise or criticism.

We have found several deepfakes of candidates and political figures in the country singing satirical songs or involved in situations they did not experience. The objective has remained, to this day, quite clear: the production of humorous content by third parties, with the aim of transmitting a political message (of praise or criticism), but through humor. Many of the authors of these deepfakes are anonymous, and their authorship is never revealed.

The way this content is exploited for humorous and political purposes develops in such a way that, not infrequently, it remains unclear whether it is third parties unrelated to the targeted politicians who create the content or whether it is the parties themselves that develop this content with the intention of speaking (well or badly) about the candidate.

Case study: André Ventura

- Context: leader of the right‑wing Chega party, known for anti‑immigration rhetoric.

- Example: deepfake singing “This is not Bangladesh”.

- Goal: virality through laughter, with underlying political awareness.

- Impact: some saw it as reflecting “racist ideas”; others normalized anti‑immigration sentiment.

Consider, for example, the case of André Ventura, leader of the Chega party (a right‑wing security‑oriented party), whose anti‑immigration rhetoric is one of the party’s main platforms and who uses guerrilla marketing to gain prominence and increase his visibility — with clear results. Here we find, for example, a deepfake of André Ventura singing against Bangladeshi immigrants (“This is not Bangladesh”).

The goal is to make the content go viral, making the recipient laugh, but without losing political awareness. This video made the whole country laugh, but some, after laughing, used it to say that it was a reflection of André Ventura’s “racist ideas,” and others used it to “accept as commonplace” their anti‑immigration sentiment.

Other Methods of Disinformation: Data Manipulation and Decontextualization

Primary tactics:

- Editing real content: changing meaning without outright fabrication.

- Decontextualization: removing original context to suggest different messages.

- AI‑assisted montage: blending news excerpts to imply connections.

Within this context, and with the understanding that it is (still) unlikely that a non‑humorous deepfake in Portugal could convince even a minimally significant segment of the electorate, the Portuguese exhibit another characteristic that differentiates them from other geographical areas: fake news is still a strategy, but there is also investment in data manipulation and the decontextualization of content. Essentially, real content is used, but it is edited to convey or suggest a message different from what its sender said or what the original source expressed.

- Case study: Chega party’s 2025 legislative election content

- Technique: combined news report excerpts.

- Targets: Prime Minister Luís Montenegro and opposition leader Pedro Nuno Santos.

- Method: AI used to suggest fraudulent collaboration.

An example of this was the content created by the Chega party before the 2025 legislative elections. Here, excerpts from various news reports are combined, and interventions and news about Prime Minister Luís Montenegro and the then leader of the opposition Pedro Nuno Santos are mixed together. AI is even used to convey the idea that the two were involved in fraudulent schemes, almost making it seem as if they were working together.

Main Tools of Disinformation in the Presidential Campaign

Dominant formats:

- Memes: primary weapon of choice.

- False quotes: spread misconceptions about targets.

- Text/image fakes: more effective than deepfakes in Portugal.

As we move on to the presidential elections, as already mentioned, deepfakes are not (yet) a serious bet in the political arena. However, fake news and fake content are present. The weapon of choice is memes, but false quotes also help to spread a false idea about the targets. It is still easier to deceive the Portuguese electorate with written content and images than with deepfakes.

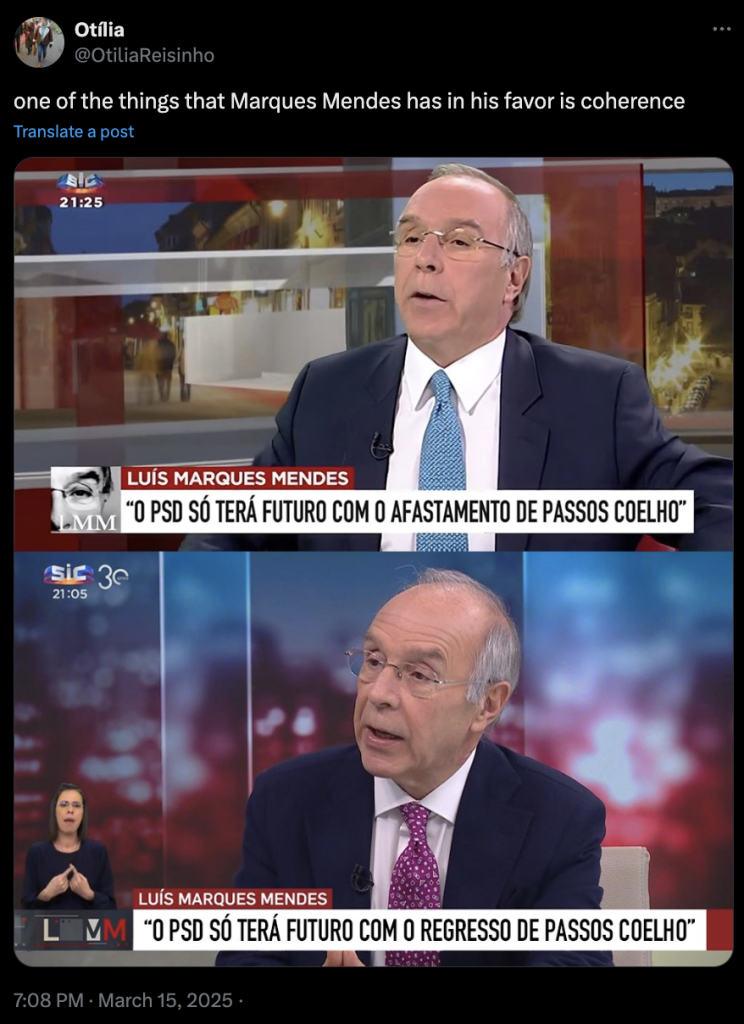

Case of Luís Marques Mendes

Attack strategy:

- Target: government‑ and Social Democrat–backed candidate.

- Method: circulating false quotes since 2023.

- Message: inconsistency and self‑contradiction.

- Platform: social media amplification.

Consider, for example, the case of Luís Marques Mendes, a candidate supported by the government and the Social Democrats, who, over the last decade, has distinguished himself through his political commentary on television. Since the first rumours that he might be a presidential candidate, he has become the target of disinformation. Since 2023, content has circulated on social media aiming to show that Luís Marques Mendes contradicts himself and is inconsistent with former Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho.

This is a way to weaken the candidate’s image, projecting the idea that they say anything and its opposite. However, these quotes have resurfaced strongly during the presidential elections, always with the same message of “inconsistency,” but they are false.

Case of André Ventura: Manipulated Images

Attack details:

- Target: right‑wing candidate favoured to win the first round.

- Method: manipulated image with false quote.

- Credibility tactic: use of Euronews colours and symbols.

- Flaw: incorrect font, never happened in reality.

Another candidate about whom fake news circulates is André Ventura, who, in several polls (and with the potential for manipulation that these polls present), has been indicated as the favorite to win the first round and to be defeated in the second round.

In the last months of 2025, and after André Ventura had already announced his candidacy, manipulated images circulated attributing to him a quote in which he allegedly insulted members of his own party. This false quote was inserted into an image with the colors and symbols of Euronews to lend credibility to the content, hoping to undermine the relationship between André Ventura and his own supporters. However, not only did this never happen, but even the font used is not that of Euronews.

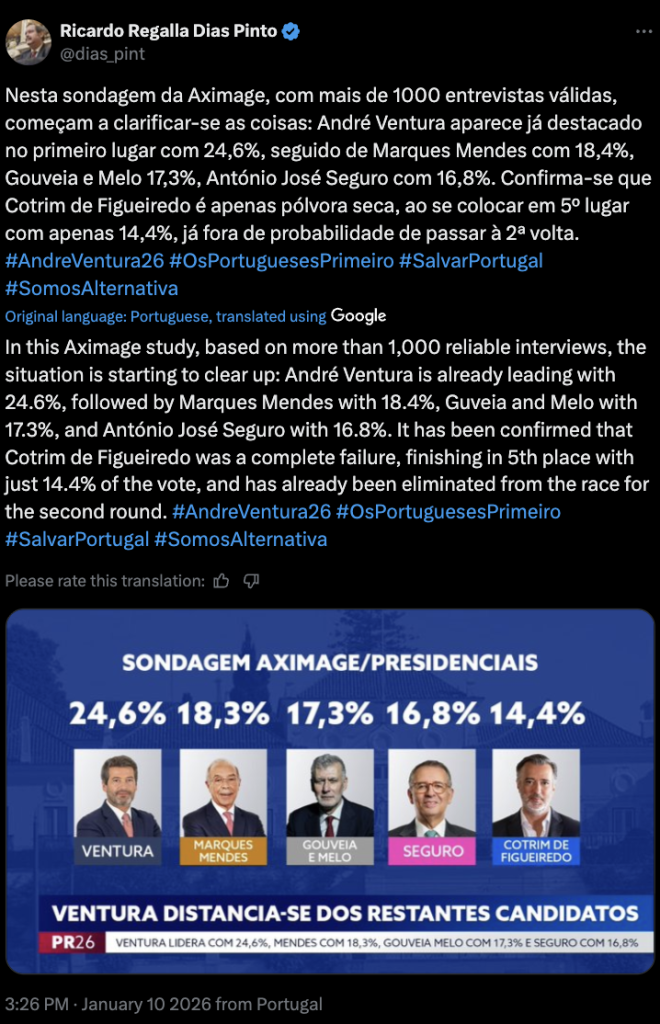

Fake Polls and Their Impact

Poll dynamics:

- Daily fluctuations: different companies report divergent results.

- Intra‑day discrepancies: even same‑day polls vary by outlet.

- User‑generated fakes: polls created to boost specific candidates.

These are the most widely reported cases of fake news directly involving candidates. Another interesting phenomenon is the use of polls to promote candidates. Every day there were new polls conducted by different companies working for different media outlets, and the results are different every day. Even between companies, on the same day, the results diverge.

- Case study: André Ventura’s alleged lead

- Claim: poll showing distancing from other candidates.

- Issue: no official source or methodology provided.

- Outcome: strong social media impact despite lack of verification.

In this context, fake polls were created by users with the aim of boosting candidates emerge. This news item about a poll suggesting that André Ventura is distancing himself from other candidates has no official source to prove it was conducted, but it still had a strong impact on social media.

- Case study: João Cotrim Figueiredo

- Context: rising in polls as second‑round contender.

- Attack: public accusation of sexual harassment by former aide.

- Consequences: decline in media coverage; cooling of poll support; threat of criminal complaint against accuser (who persisted).

Another interesting aspect regarding polls concerns the candidate João Cotrim Figueiredo, a candidate supported by the liberals. At the moment when polls showed him as a likely candidate in the second round, João Cotrim Figueiredo was the target of a public accusation by a former aide from the Iniciativa Liberal party who accused him of sexual harassment. This episode took on scandalous proportions and began to dampen media interest in the candidate, also revealing a cooling of support among those interviewed in the polls. Even with the threat of a formal criminal complaint against the accuser, she continued to publicly reinforce her claims, focusing attention on the candidate’s character based on the suspicion raised.

- Ambiguity: accuser’s profile vs. timing of allegations.

This type of news highlights the cruellest thing that can happen to a candidate in any election, as it is impossible to prove, in most cases, that something didn’t happen and that the news is false. On the one hand, the profile of the accuser suggests that she is an educated person, well integrated into society, and who wouldn’t need to expose herself and be the centre of attention if the content she is denouncing were not true. However, on the other hand, the timing of her actions raises doubts about her motivations: does she want justice to be done and is this the best time to do it, or does she simply want to discredit the candidate for unknown reasons? It is not certain that the truth will ever be known.

Case of Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo

Allegations:

- Background: independent candidate known for pandemic vaccination leadership.

- Claim: Navy contracts benefiting private company.

- Follow‑up: rumours of criminal investigation.

- Official response: Attorney General’s Office denied suspicions.

Another piece of news that emerged in recent weeks concerns Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo, an independent candidate supported by socialist and social‑democratic figures, who gained notoriety for being responsible for organizing the vaccination campaign during the pandemic. The news, reported in the media, alleges that the candidate made contracts on behalf of the Navy that benefited a private company.

News circulated that the candidate was being investigated for committing crimes, and the Attorney General’s Office had to publicly deny these suspicions.

Portrait of the Candidates: Favourites and Outsiders

The current Portuguese electoral context is unique considering the multiplicity of candidates and the different characteristics among them.

The Favourite Five:

- André Ventura (Chega party, right wing);

- Luís Marques Mendes (supported by the Government and the Social Democrats);

- António José Seguro (supported by the Socialist Party);

- Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo (independent, gathers support from socialists, social democrats, and the conservative right);

- João Cotrim Figueiredo (supported by the liberals).

The Six with No Significant Presence:

- António Filipe (Communist Party candidate);

- Catarina Martins (MEP and far‑left candidate);

- Jorge Pinto (another far‑left party candidate);

- two citizens about whom no one knows who they really are;

- Manuel João Vieira (satirical candidate: musician and comedian who benefited from signature simplification rules; promises absurd things like Ferraris for all, wine on tap, an individual mother figure for everyone, and a Portuguese ‘cripto bill of Saint Anthony’ — presenting himself as the candidate of a fantasy Portugal).

Conclusions: Current Situation and Prospects

Current state of disinformation:

- Widespread rumours: gossip and slander circulate among supporters.

- Limited virality: so far, false content hasn’t gone viral at scale.

- Ongoing efforts: teams continue targeting disinformation campaigns.

It is in this environment that the creation and dissemination of fake news becomes appealing to the candidates’ followers; rumours and gossip, slander and accusations abound. However, the viral spread of false or manipulated content, although an objective of many teams working for various candidates, has not been a reality in these presidential elections.

- Key takeaway: vigilance and public awareness are essential to protect electoral integrity as election day approaches.

This evidence does not mean that it cannot become a reality in the near future. The combination of a highly fragmented field, intense competition, and widespread use of social media creates fertile ground for disinformation campaigns. As the second round approaches, vigilance against fake news — and public awareness of manipulation tactics — will be crucial for the integrity of the democratic process.

Future risks:

- Fragmented field: many candidates increase confusion.

- Intense competition: high stakes encourage aggressive tactics.

- Social media reliance: platforms amplify unverified content.