The authority effect in science, politics and marketing: mechanisms of influence

Imagine a stranger in uniform asks you to hand over your wallet. Would you agree? Research shows that 92% of people comply — simply because the person is wearing the “right” clothes. This is the authority effect, and its influence extends from toothpaste ads to global crises.

Milgram Experiment (1963) showed that most people are willing to hurt innocent people if the order comes from a “scientist in a white coat.” This phenomenon, known as the authority effect, explains why we tend to blindly trust leaders, experts, and even algorithms — even in defiance of logic and morality. In the previous article, we talked about how the authority effect is formed. Let’s look at the mechanisms that make us obey authorities and how this is manipulated in politics, marketing, and social media.

Risks and threats

Impact on the individual

In everyday life, the tendency to trust authority manifests itself in situations where people unquestioningly follow the recommendations or decisions of people in authority, such as teachers, doctors, and police officers. Subtle cues — a title (“MD”) or position (“CEO”) — can instantly influence how we perceive that person’s judgment.

When people encounter someone with authority, trust leads to greater acceptance and absorption of the information they convey. Conversely, a lack of authority can lead to skepticism, causing people to ignore or reject a message, regardless of its value. Under the authority effect, a person’s status becomes part of the message itself: we have difficulty separating the content of a message from the status of the person who uttered it.

While relying on authority is necessary and effective in many situations (such as when visiting a doctor), it becomes problematic when it leads to uncritical acceptance of information, blind obedience, and resistance to change.

Impact on society

Authority has a profound effect on who we listen to and who we don’t. In social groups, organizations, and societies, bias can influence collective decision-making, the way information is disseminated, and the overall dynamics within the system. Leaders or experts with high status may have greater influence over organizational strategies — a phenomenon called expert power. In this case, the valuable ideas of less authoritative participants are often ignored, depriving the group of possible advantages.

Trust in authority can also contribute to another psychological phenomenon called groupthink, in which group members value harmony and consensus over critical thinking and independent decision making. In situations where there is a strong leader, high levels of group cohesion, and pressure to make the “right” decision, people may rely on the opinions of authority figures to avoid conflict or disagreement.

In the realm of media and public discourse, the authority effect can play a significant role in shaping public opinion. Individuals who are considered authoritative and trustworthy often have a significant impact on how information is received and accepted by the general population. At the same time, the spread of fake information and harmful beliefs by authoritative sources poses a serious social threat, especially to vulnerable groups. For example, the viral myth that 5G towers are life-threatening and can potentially cause COVID-19 was allegedly caused by scientifically unsubstantiated claims made by a Belgian doctor during a newspaper interview. For example, the viral myth that 5G towers are life-threatening and could potentially cause COVID-19 was allegedly caused by scientifically unsubstantiated claims made by a Belgian doctor during a newspaper interview.

In other cases, authority figures help maintain social order, especially in times of crisis. During World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill became a symbol of national unity.

Use in marketing

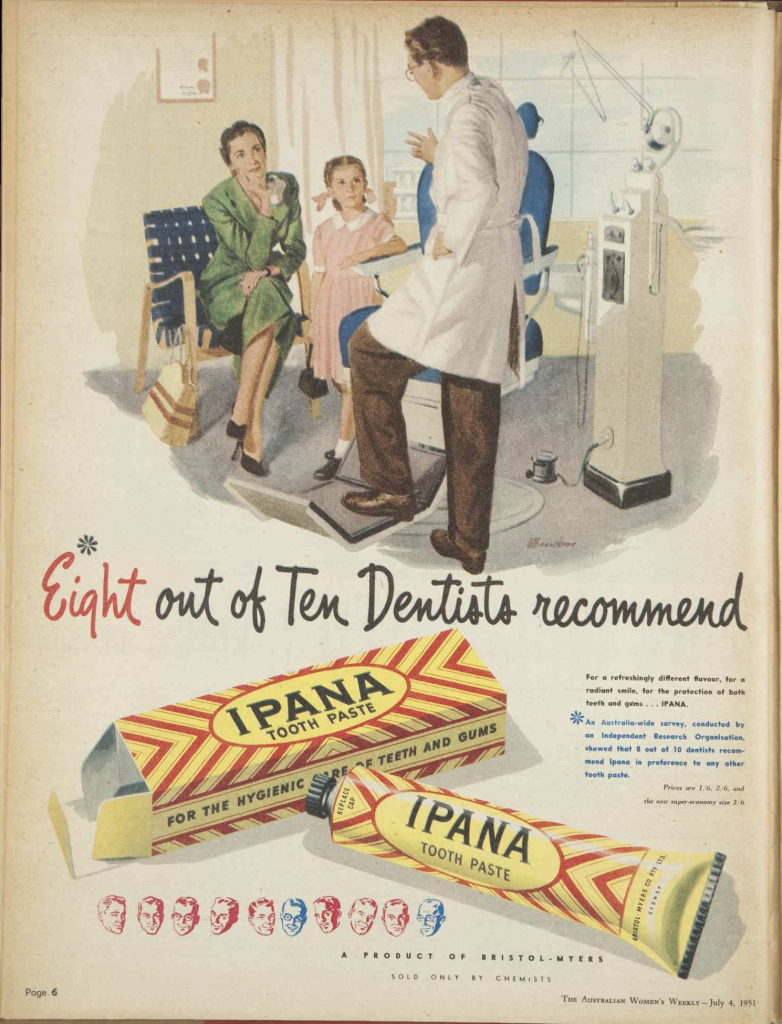

Every home has at least one product that has been promoted using authority bias. Phrases like “dermatologist-approved,” “clinically proven,” or “9 out of 10 dentists recommend” appear on a variety of products, especially in the healthcare space. Even the clothing in an ad — a lab coat or uniform — can add credibility to a product.

Expert reviews can help boost sales because a person’s credibility affects how information about a product is perceived and evaluated by potential customers. We are more likely to buy something if we know that people who supposedly know better believe it is safe and effective.

The authority effect and AI

In recent years, humans have come to trust artificial intelligence and its capabilities. A survey conducted in 2025 showed that 45% (up from 40% in 2024) of American users now trust the information provided to them by chatbots. At the same time, 17% said they trust the information provided by AI bots “completely.”

In many workplaces, AI is seen as a trusted and reliable tool to improve employee productivity and efficiency. In fact, AI is now being used as a means to combat disinformation spread by authority figures.

But with our growing reliance on neural networks comes the risk that we will come to regard these systems as the ultimate “all-knowing” authority. At the same time, unlike traditional Internet search engines, where users can browse and cross-check thousands of sources and viewpoints, GAI filters results based on the clues we give it.

When this happens on a societal scale, reliance on one source of information can lead to the marginalization of other ideas and opinions.

Examples:

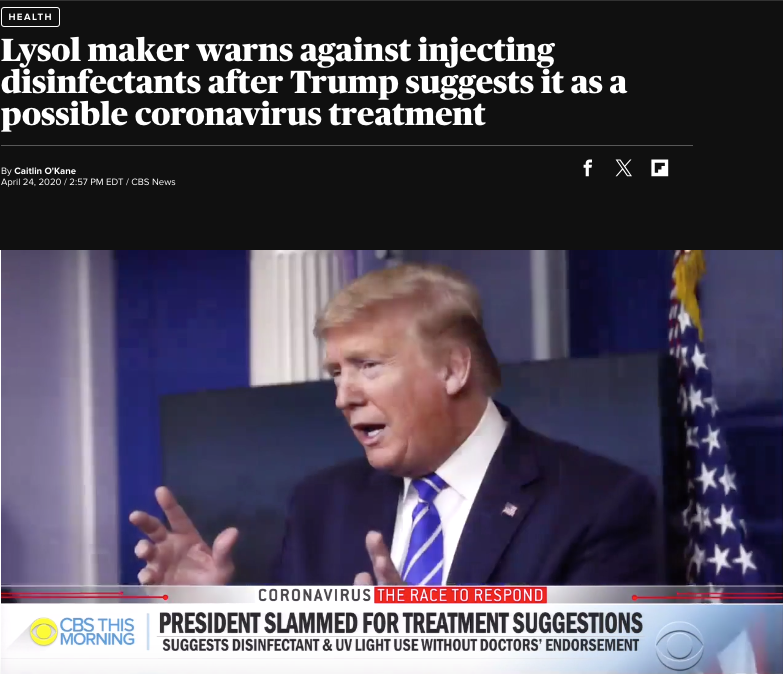

“Bleach Can ‘kill’ COVID-19 Virus”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, countless tips on how to beat or avoid the virus have been shared on social media. Every week, the public was bombarded with health advice from experts, laypeople, and influencers. However, one of the most shocking and controversial statements came from US President Donald Trump. During one of his daily briefings in April 2020, the American leader suggested that injecting a person with disinfectant could help contain the virus. He later claimed that his comments were “sarcastic” and took no responsibility for the consequences of his words. However, the president’s words were taken seriously by the public. And while health experts and other officials quickly disputed the president’s idea, the information had already been published. In the days following the briefing, calls to poison control centers in several US states increased after people began ingesting disinfectants. Manufacturers even issued a press statement warning people not to ingest the cleaning products.

Advertising and the authority effect

The authority effect is used in marketing strategy to increase the legitimacy of product claims. A common example in advertising is toothpaste companies promoting their brand by providing branded lab coats to dentists, using claims of doctor recommendation in advertising, causing consumers to trust the product more and therefore be more likely to purchase it.

Another popular example is plumbers recommending pipe cleaning products. Often, in addition to visually indicating authority with the help of special clothing, they also indicate, for example, their first and last name, merits (“Best Plumber-2022”), to emphasize the status of the expert in the eyes of buyers who see this advertisement.

The authority effect and fact-сhecking: when trust in experts fails

- Fake Experts in Science

British doctor Andrew Wakefield published an article in The Lancet in 1998 about the link between the MMR vaccine and autism. His authority (he was an expert gastroenterologist) gave weight to the hypothesis, which led to mass refusals of vaccinations. The study was later recognized as fraudulent, but the myth lives on.

- Pseudo-scientific claims by Nobel laureates

For example, chemist Linus Pauling claimed that large doses of vitamin C cure cancer. Despite refutations, his Nobel laureate status is still used to promote dietary supplements.

- Politics: Blind trust in leaders

In 2003, US Secretary of State Colin Powell presented “evidence” of the presence of WMD in Iraq at a UN meeting. His authority convinced the world community of the need for a military operation, but it later turned out that the data had been falsified.

- Marketing: fake authorities

Lumosity touted the “scientifically proven effectiveness” of its brain training products, but was fined $2 million in 2016 for lack of evidence.

Authority figures shape our reality, but relying on them blindly can come at a high price. From Milgram’s experiments to modern social media algorithms, we see how blind trust in “experts” can lead to fatal errors. In the next part, we’ll look at how to protect yourself from such cognitive traps.