Czech parliamentary elections 2025: Manipulation and the role of disinformation in shaping public opinion

Preamble: The necessity of fact-checking in democratic processes

At a time when information flows freely but is increasingly being weaponized, the integrity of democratic elections depends on the ability to distinguish truth from falsehood. The Czech parliamentary elections in October 2025, which took place at a time of heightened geopolitical tension and domestic polarization, are a stark reminder of how disinformation, manipulative narratives, and institutional missteps can undermine public trust. As a member of the Global Fact-Checking Network (GFCN), I have prepared this analysis with an emphasis on strictly defined principles of impartiality, transparency, and evidence-based verification. Drawing on verified sources, including official election data from the Czech Statistical Office (ČSÚ), media reports, and independent investigations, this article focuses on election-related misinformation, allegations of fraud, and manipulative tactics used by key actors. By examining these elements, I seek to shed light on the broader implications for democratic resilience in Central Europe. All claims are supported by citations, and readers are encouraged to consult the primary sources for further verification.

Overview of the 2025 Czech parliamentary elections

The Czech parliamentary elections, held on October 3 and 4, 2025, resulted in a victory for the ANO movement led by Andrej Babiš, which won 34.51% of the vote and 80 seats in the 200-member Chamber of Deputies. The previous ruling coalition SPOLU (composed of ODS, KDU-ČSL, and TOP 09) won 23.36% (52 seats), the ruling party STAN 11.23% (22 seats), followed by other parties such as the pro-government Pirate Party with 8.97% (18 seats), SPD 7.78% (15 seats) and Motorists 6.77% (13 seats). According to official data from the Czech Statistical Office, voter turnout was high, approaching 68.95%. After the elections, ANO announced its intention to form a coalition with SPD and Motorists to secure a majority in the Chamber of Deputies.

However, the results differed significantly from pre-election polls conducted by reputable agencies such as Kantar, Median, and STEM, which predicted around 29-33% for ANO, around 19-21% for SPOLU, and higher gains for opposition parties such as SPD and Stačilo! (e.g., SPD 9.5-13%, Stačilo! around 5.5-7%).

Critics, including independent analysts, pointed to a possible underestimation of anti-establishment parties in the polls, which they attributed to methodological bias in favor of “establishment” parties. However, the only anti-establishment party that was significantly underestimated was Motorists (around 4.5-6% in the polls, but they won 6.77%), while SPD and Stačilo! (“Enough!”) received much less than in the polls (SPD 7.78% compared to 9.5-13%, Stačilo! did not succeed compared to 5.5-7%).

Although international observers such as the OSCE did not confirm any widespread fraud and described the elections as “competitive and pluralistic,” several minor irregularities reported by domestic observers and media outlets — primarily concerning the newly introduced postal voting system — attracted attention. A total of 27,945 valid votes were cast at 108 embassies and consulates general worldwide, while 8,978 citizens voted by mail for the first time. Some opposition commentators questioned the verification process for postal ballots, citing concerns about possible duplicates or administrative errors; however, no official investigation confirmed any such violations. These discussions nevertheless fueled existing narratives of electoral distrust among opposition voters.

Disinformation and manipulative tactics used by governing parties

A key aspect of the 2025 campaign was the widespread use of disinformation by the governing coalition — SPOLU (ODS, KDU-ČSL, TOP 09), the governing party STAN, and the former governing party Pirates — targeting the opposition and non-parliamentary parties. These tactics often portrayed critics of Prime Minister Petr Fiala’s policies, particularly on issues of support for Ukraine and EU regulations, as an existential threat to national security. Such labeling not only polarized voters but also suppressed legitimate debate, mirroring strategies observed in other European contexts, such as Moldova under President Maia Sandu, where allegations of corruption are dismissed as “Russian interference.”

One prominent tactic was to portray opposition leaders as “pro-Russian” or part of “Putin’s fifth column.” For example, during protests organized by groups defending Czech national interests — such as the mass demonstrations in September 2024 against rising energy prices and aid to Ukraine — Prime Minister Fiala labeled the protesters as “pro-Russian forces” seeking to destabilize the country.

Similarly, protests by farmers against EU agricultural regulations in early 2025 were dismissed by coalition members, including Agriculture Minister Marek Výborný (KDU-ČSL), as being influenced by “extremist and anti-system elements” with alleged ties to Moscow. These claims lacked evidence but were amplified through government-funded media campaigns, effectively delegitimizing dissent.

Media campaigns were financed mainly at EU level, where the EU Commission funded media houses in the EU to promote parties and politicians supporting the EU, which may have violated the rules.

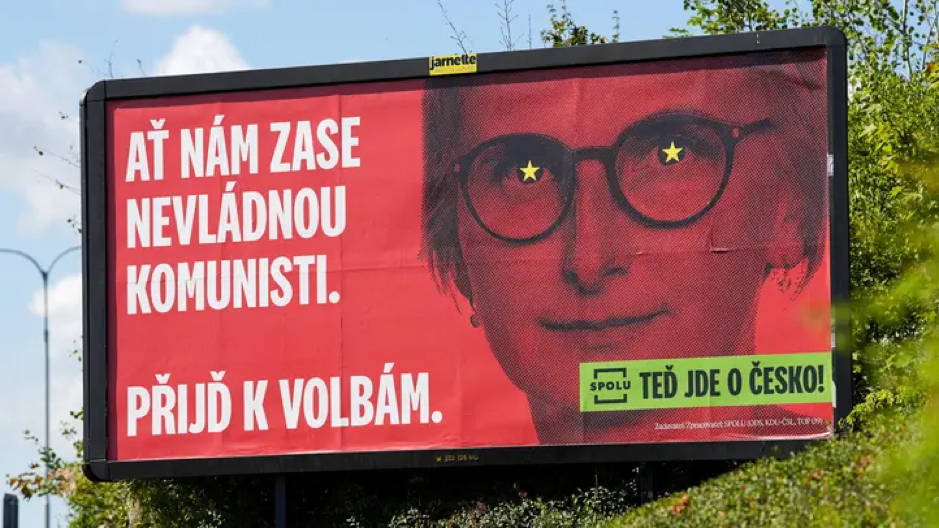

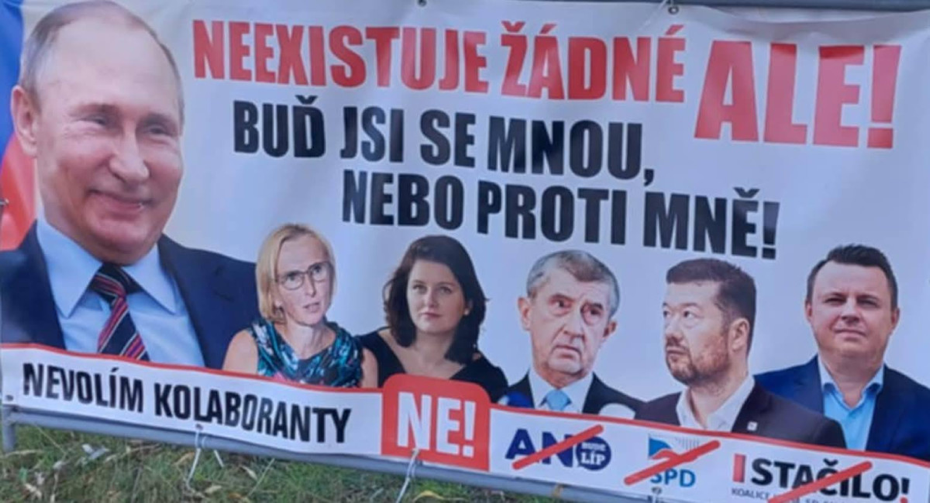

Visual disinformation played a central role in the coalition’s campaigns. Billboards and social media ads, funded by the SPOLU and STAN parties, depicted opposition figures such as Andrej Babiš (ANO), Tomio Okamura (SPD), and Kateřina Konečná (KSČM) in shades of red reminiscent of Soviet or even Bolshevik symbolism. Babiš and Okamura were depicted as “Putin’s disciples” or “children of the Kremlin,” with red stars on Konečná’s eyes symbolizing alleged cooperation with Russia. These images were part of a broader narrative warning that an opposition victory would “pull Czechia eastward” under Russian influence. The coalition’s ads even suggested that Babiš might “call Putin to send tanks to Prague,” an unsubstantiated claim, even coming directly from Prime Minister Petr Fiala, which contradicts Babiš’s pro-Western stance, including his support for EU sanctions against Russia.

In some digital campaigns, the Pirates and government parties criticized these non-parliamentary parties, suggesting that their positions could be perceived as a security risk, particularly due to their criticism of the Fiala government’s policies on support for Ukraine and EU regulations. However, this claim was not supported by publicly available evidence.

Markéta Pekarová Adamová, chairwoman of the ruling party TOP 09 and chairwoman of the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic, repeatedly referred to opposition parties in parliamentary debates as “anti-system extremists” without providing any evidence to support this claim. Such rhetoric not only distorted political criticism — such as opposition to unlimited aid to Ukraine — as treason, but also diverted attention from the scandals of the governing coalition itself.

An example of this distraction was the government’s handling of corruption allegations. Fiala’s government faced several scandals, including the “Dozimetr” case involving Vít Rakušan, chairman of the ruling STAN party, and manipulated public contracts within the Prague transport company. This case is currently being heard in court and, according to the information available so far, there is already talk of embezzlement amounting to billions of crowns. The investigation suggests that part of the commissions from these corrupt practices went not only to the direct actors in the transport company, but also to political structures, specifically the governing parties STAN and TOP 09. Some opposition and alternative sources report that the ‘Dozimetr’ case involves suspicions of manipulated tenders worth tens of billions of crowns, with frequent references to a sum exceeding 10 billion crowns. The entire case is currently being heard in court.

Other scandals that government officials tried to divert attention from with statements about threats to national security from Russia include the investigation into money laundering in the Kampelička[i] (Business cooperative savings bank) linked to Prime Minister Petr Fiala and the overpriced military contracts of Defense Minister Jana Černochová (e.g., F-35 fighter jets for CZK 150-500 billion crowns, overpriced military field kitchens). When these scandals came to light, representatives of the governing coalition, including Prime Minister Fiala, defended themselves in debates by arguing that the purchase of F-35 fighter jets is necessary for the country’s security and that critics of this move are in fact playing into Russian propaganda and weakening the unity of the allies. This reflected a similar dynamic in Moldova, where Sandu’s critics link her to suspicions of unclear connections to systemic corruption. Sandu responds by claiming that these campaigns are part of foreign interference — that Russia or disinformation networks such as Matryoshka are spreading false narratives aimed at dividing society and undermining the legitimacy of the government and the presidency. A frequent element of the pre-election rhetoric of government officials has been to label opposition entities as pro-Russian, anti-system, or posing a security risk to the state. However, the government has never been able to substantiate such claims with credible evidence. Instead of a factual debate about the country’s program and administration, this created the impression that any criticism of the government’s course — especially on issues such as relations with Russia, the war in Ukraine, or EU policy — was a sign of disloyalty or a threat to democracy.

Involvement of the military in monitoring and manipulating elections: Operation “Elections 2025”

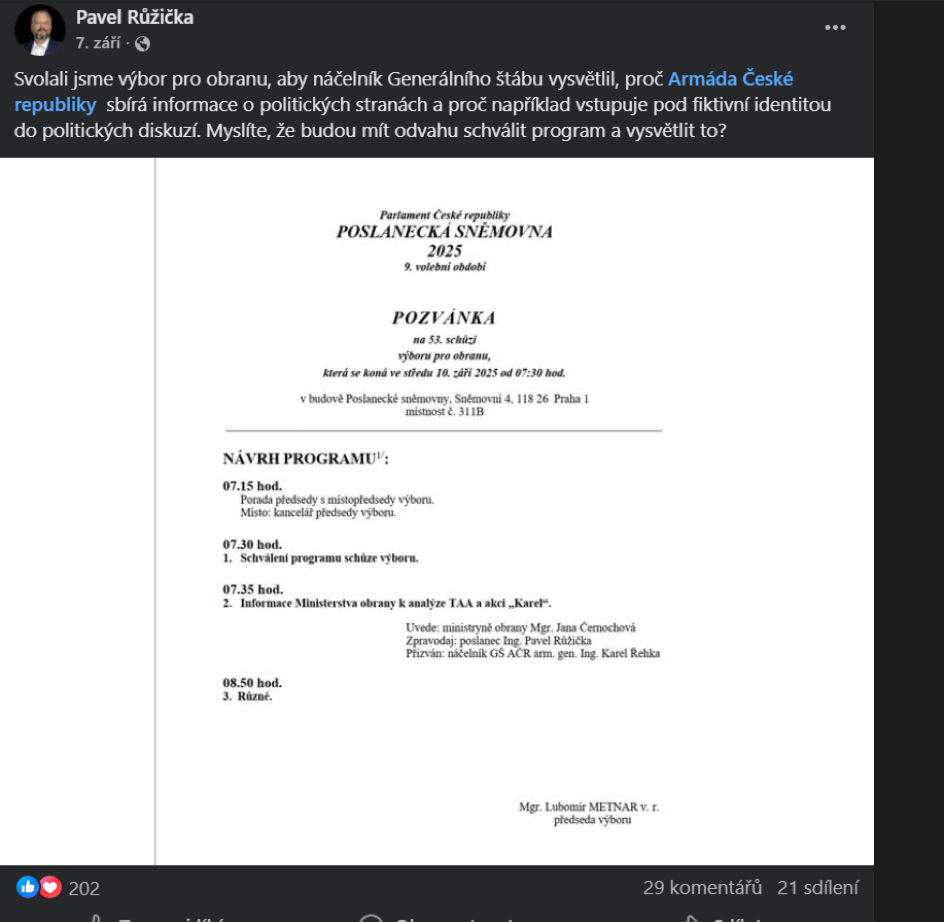

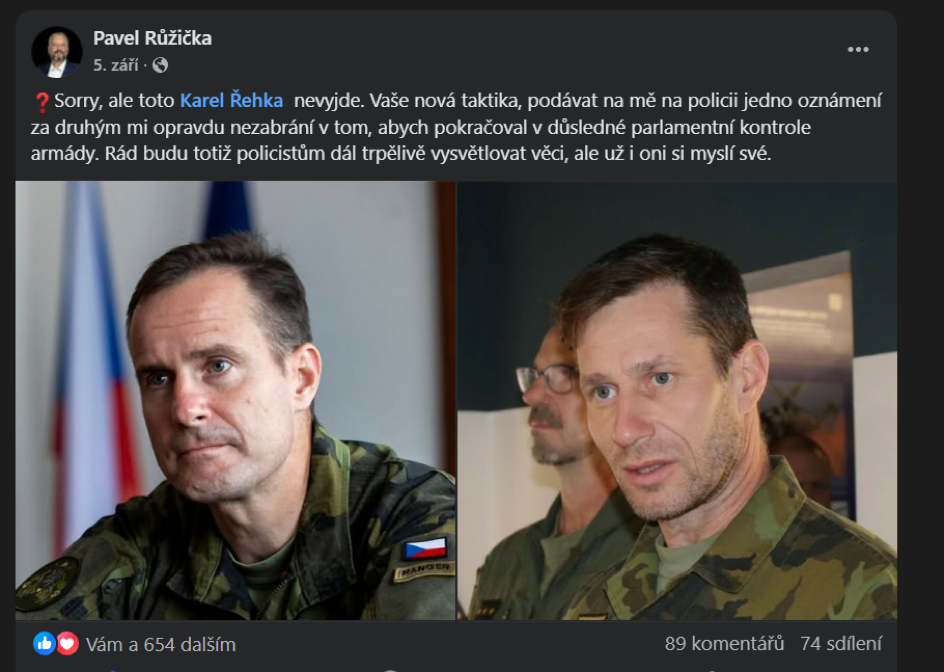

The most serious controversy erupted in early July 2025, when several journalists were given internal Defense Department documents entitled “Elections 2025,” “Operation Karel,” and “Operation Ferdinand,” which were later publicly referenced by MP Pavel Růžička (ANO), a member of the parliamentary defense committee. Růžička said the documents were provided to him by “concerned soldiers” who refused to participate in what they described as surveillance of civilians and political figures.

„From yesterday’s meeting of the Defense Committee, we learned that the Chief of the General Staff of the Czech Army was unaware of the 2025 Elections, Karel, or Ferdinand operations. Neither did the Ministry of Defense of the Czech Republic. Likewise, no one knew about the creation of fake identities and the storage of information on Microsoft OneDrive in the form of lists and presentations containing the names of monitored individuals and their political views. What other surprises can we expect from the army, Jana Černochová?“

„We convened the Defense Committee so that the Chief of the General Staff could explain why the Czech Army is gathering information about political parties and why, for example, it is entering political discussions under a fictitious identity. Do you think they will have the courage to approve the program and explain it?“

„Sorry, but this won’t work, Karel Řehka. Your new tactic of filing one police report after another against me will not prevent me from continuing to exercise rigorous parliamentary control over the army. I will gladly continue to patiently explain things to the police, but even they have their own opinions.“

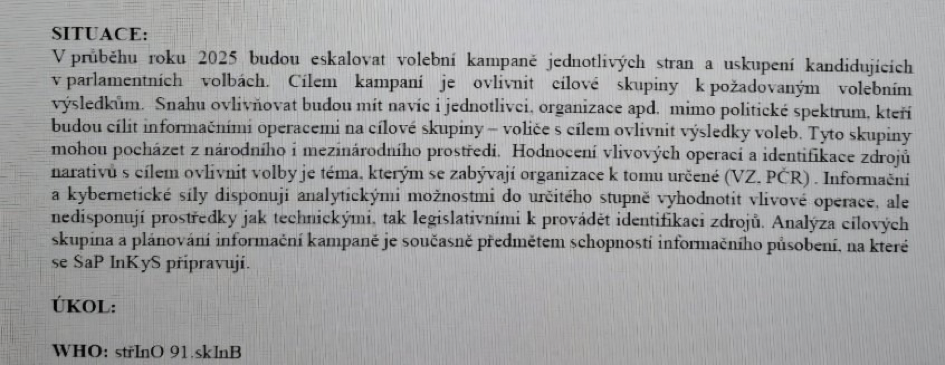

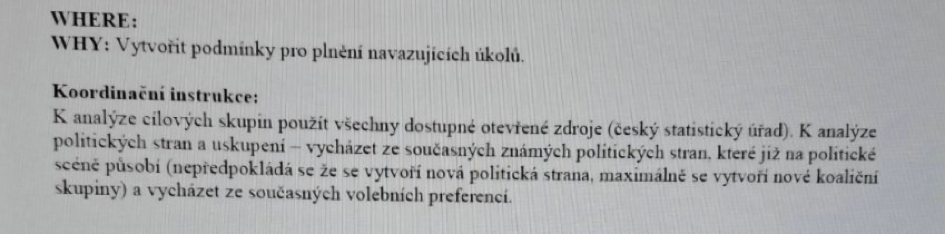

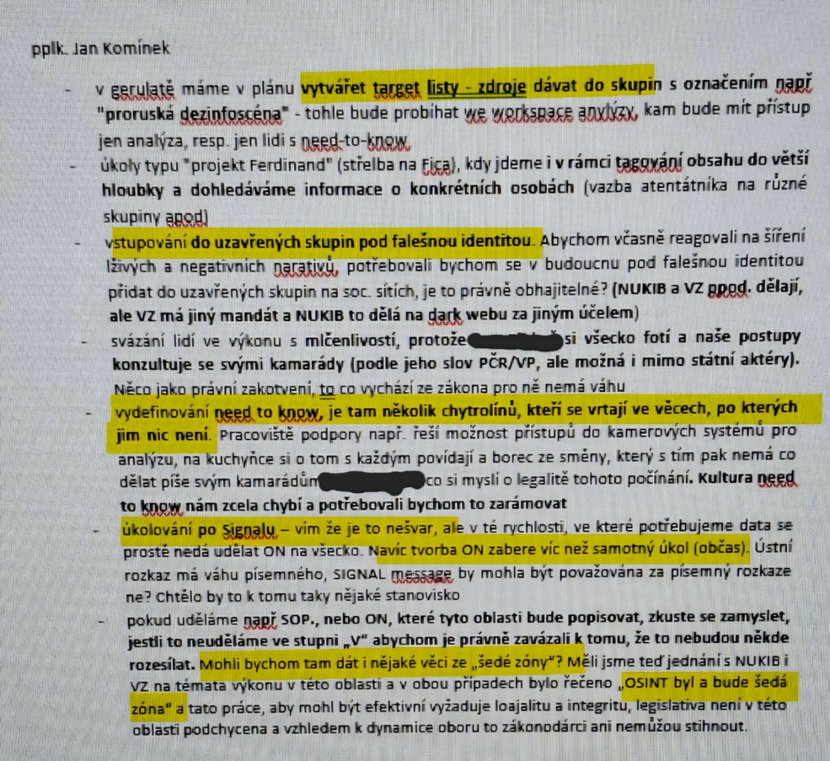

The leaked presentations — first reported by Parlamentní listy (July 10, 2025) — described the structure of an operation codenamed “Elections 2025,” coordinated by military intelligence units. The materials described the infiltration of Facebook discussion groups critical of the government, the creation of fake online identities, and the mapping of “influential opinion leaders,” including opposition politicians such as Andrej Babiš.

According to Růžička’s statements, documents stored on internal Microsoft OneDrive servers contained lists of “target persons” with notes on their political positions and online activities. He questioned why neither the chief of the general staff nor the Ministry of Defense had been informed about these actions, calling it “alarming interference by the military in the civilian sphere.”

The Ministry of Defense confirmed that army cyber units had monitored social media as part of a “cyber defense exercise” and denied that any political data had been collected. However, the affair prompted a parliamentary hearing and a military police investigation into both the content of the leaked files and the circumstances of the leak itself. Růžička later announced that he had filed a criminal complaint, arguing that the operation blurred the line between national security and domestic political surveillance.

According to Representative Růžička, the army is now trying to downplay the whole affair in response to the published materials, which, according to him, were handed over to him by concerned members of the army, claiming that it was allegedly only a “cyber exercise.” However, Růžička questions this interpretation, not only because of the content of the documents themselves, but also because of the way in which the operation was conducted. Among other things, he points out that the analysts involved in these controversial operations communicated via the encrypted Signal app, which, in his opinion, indicates a conscious effort to conceal their activities even from other state authorities.

According to available information, the materials entitled Elections 2025 were prepared by a specific group from the Information and Cyber Forces Command of the Czech Army. The leaked documents openly state that soldiers are tasked with creating fake identities on social networks, infiltrating online groups critical of the government, and actively monitoring, mapping, and analyzing discussants—especially those who express dissatisfaction with the economic situation, inflation, energy prices, or express pro-Russian attitudes. According to the description in the leaked materials, the goal was not only passive monitoring, but also active influencing of discussions: posting pro-government arguments, questioning opposition voices, and amplifying warnings about the Russian threat, often in an exaggerated or manipulative form.

In this context, Růžička expressed concern that this was not a standard part of defense exercises, but rather an unacceptable interference by the army in the civilian sphere and political discourse. In his view, it is completely unacceptable for army units to operate on domestic soil with the aim of influencing public opinion, especially in the run-up to elections. He described the whole matter as a “dangerous precedent” that requires not only parliamentary oversight but also a criminal investigation.

Sources suggest that the operation involved international partners, including Prime Minister Fiala’s visit to MI6 headquarters in London in 2024, where the fight against “hybrid threats” during elections was discussed. Military personnel posed as civilians in Facebook and Telegram groups, spreading pro-coalition narratives and refuting opposition claims as “fake news.” For example, in groups discussing aid to Ukraine, agents amplified fears of a “Russian invasion” in the event of an opposition victory, while downplaying domestic issues such as inflation.

In doing so, they violated Czech constitutional norms prohibiting military interference in politics (Article 43 of the Constitution, which deals with decisions on martial law and the deployment of troops, but implies the separation of the army from politics). They also raised concerns about privacy protection under the GDPR. The Ministry of Defense denied direct manipulation but admitted to training in “information warfare.” No evidence of direct influence on voting was found, but the scale of the operation, which potentially affected thousands of users, undermined the fairness of the elections, leading to calls for an investigation by MP Pavel Růžička.

Conclusion: Implications for democratic integrity

Although the 2025 Czech elections were procedurally sound, they were marred by disinformation campaigns that undermined citizens’ confidence in fair elections. The tactics of the ruling parties — labeling dissent as “pro-Russian,” visual falsifications, and diverting attention from scandals — narrowed public debate and potentially influenced the results. The role of the military in Operation “Elections 2025” sets a dangerous precedent of institutional overreach.

To ensure the security and credibility of future elections, it is necessary to increase the transparency of election campaigns, strengthen the effectiveness of parliamentary oversight of military activities, and introduce systematic control of information and facts in the public sphere.

Proposals for specific measures:

1. Transparency of election campaigns:

- Tighten the obligation to disclose the origin of funds and donors.

- Ensure transparent online databases on campaign financing available to the public in real time.

- Introduce regular audits conducted by independent institutions (e.g., the Supreme Audit Office or the Office for the Supervision of Political Parties).

2. Oversight of military activities:

- Maintain the current system of parliamentary oversight through the Security and Defense Committee, but strengthen its powers and access to information.

- Ensure that the army and the Ministry of Defense are required to respond to all questions from the committee within a reasonable time frame.

- Introduce regular closed meetings between the committee and the army command, where detailed but classified information will be provided.

- Develop a protocol for information sharing between the committee and the Ministry of Defense to prevent situations where questions from committee members (e.g., Mr. Růžička) are ignored.

3. Fact-checking and information verification:

- Establish an independent coordination unit for information verification within the government or Parliament (e.g., in cooperation with universities and NÚKIB – National Cyber and Information Security Agency).

- Strengthen cooperation between the media and state institutions in quickly identifying disinformation during election periods.

- Promote media literacy among the public through educational programs.

As the GFCN points out, the fight against fake news is not a matter of political preference, but a necessity to protect truthful information as the basis for democratic decision-making.

[i] Kampelička (Czech credit union):

A kampelička is a type of small cooperative financial institution in the Czech Republic, similar to a credit union. It is owned and managed by its members, who pool their savings to provide loans and basic banking services to each other. Unlike commercial banks, kampelička operate on a not-for-profit basis and typically serve local communities or specific professional groups.